“There is a mistaken understanding that fresh expressions of Church are mostly linked to Evangelical churches and traditions. However, this is simply not true, as can be seen at the website, Fresh Expressions of the Sacramental Tradition.” writes Thomas Brauer

Good Idea is our online magazine where you’ll find inspiration, tips, ideas, and stories of how God is working in other churches. Every month we offer one good idea to help churches grow in sharing the faith.

Good Idea!

Imagining God’s World in High Definition

I’m not a big video-gamer. With that said, I need to make a confession: it’s not because I’m anti-video game but because my parents knew full well that my addictive personality would have attached itself to video games and would never have let go. So, I was never allowed to own a game system growing up; although my brother and I were allowed to rent them over a weekend once in a while which would turn into sleep-starved days of video game binging that only served to underscore my parents’ point!

I went through university and graduate studies never owning one, but I was really too busy to notice. Either that, or I was too poor to buy one, I’m not sure which. Now, I’ve got my own family and life is much too hectic to even find the time to sit down and play video games. This is all to say that video game culture has never become a part of my life, until now.

My father-in-law recently purchased a PS3 (that’s a “Sony PlayStation 3”, for those of you who are not down with the lingo) to go with his new High Definition TV. We visited a few weeks ago and our four year old son was quickly introduced to this culture. Watching him clutch the game controller was like watching a smuggler holding onto his cherished contraband as a smile of wild hilarity mixed with mischievousness gripped his face. A racing game with intense graphics and pounding music promptly became his favourite. I should admit, partly because my wife reads this column and partly because I’m honest, that I got hooked too (now, two in the morning isn’t that crazy a time to be sitting alone giddily driving a rally car across the desert is it?).

What really took me by surprise was how proficient my son became at this game. After only a few tries, he was keeping his vehicle on course, passing other cars and making good time around the track. Not only that, driving home down the highway he was giving me lessons from the back seat on exactly how to pass other cars at high rates of speed!

Regardless, what I took from this little foray into the alternative reality of “Video Game Land” was how quickly and thoroughly our children are shaped and formed by what we put in front of them. Not only that, I’m amazed at how skilled and adept, at how well versed a four year old can become in the habits and skills of this culture.

While I’m aware and convinced of the potential dangers of video-game addiction and the abhorrent nature of some of these games that make Quentin Tarantino look like a younger, edgier Walt Disney, I’m not overly interested in weighing in on this. What I am interested in is the simply fact that these ‘alternative’ realities so deeply and completely capture the imagination of our children and young people (and sometimes even a husband or two!).

Our imaginations, especially those of children, are apprehended and formed by what’s around us. What the church often forgets and neglects is that it is in the imagination business, as deeply and completely as something like the video game industry is. We don’t often think of the church in this way, but it’s imperative that we re-capture this sense of ecclesial imagination if we are to be, in any way, a witness to God’s action in our world.

At a very basic level, the church imagines a different world, not because it’s in the business of making stuff up, but because it follows Jesus who, in himself, brings God’s imagination to bear on all things. When the church gathers as followers of this Jesus, it can’t help but imagine that everything is different because this Jesus showed up on the stage of history and imagined God’s very kingdom into existence.

Much as our imagination is trained and shaped by what we spend time with—be it videogames, movies, television, the internet, or the ever-beloved IPod (a word which, by the way, my spellchecker recognizes!)—the church’s imagination is shaped and trained in its worship and in its life together. It’s in this life together, in our liturgy, where we learn to inhabit and act out this kingdom among us. Our communal reading of Scripture, our prayers, our table fellowship, and our peace-sharing are some of the habits that shape us; they are some of the spiritual disciplines that form us and ought to form our children.

But our church has often failed children and young people at the fundamental level of capturing their imaginations and worlds with the amazing and exhilarating adventure of the kingdom of God. We continually make the same mistake the disciples did—we assume that this kingdom of God stuff is grown-up and important business.

I’m fully conscious that it’s not easy for the church to keep the attention of children and young people these days. Maybe it’s because we live in a world where there is so much sheer competition vying for the attention of our children that the church is fatally doomed from the start, or maybe, just maybe, it’s because we ourselves aren’t sufficiently hooked.

God-Wrestlers

Among the misconceptions people have about the Christian spiritual life—and there are many!—is the idea that it’s somehow easy. While we have all heard variations of this theme many times, youth seem particularly vulnerable to it. For many young people, when they have had a truly significant encounter with God and begun to explore their relationship with God more consciously, there is an expectation that everything will get better and life easier. After all, didn’t Jesus say that his “yoke is easy and … burden light”?

Among the misconceptions people have about the Christian spiritual life—and there are many!—is the idea that it’s somehow easy. While we have all heard variations of this theme many times, youth seem particularly vulnerable to it. For many young people, when they have had a truly significant encounter with God and begun to explore their relationship with God more consciously, there is an expectation that everything will get better and life easier. After all, didn’t Jesus say that his “yoke is easy and … burden light”?

While there is undoubtedly a sense in which a life with God is better than one without God, it’s not a simple path of magic. Here, ‘better’ has nothing to do with false ‘prosperity gospel’ promises, and it most certainly doesn’t mean that life is easier. It can, in fact, get more complicated and difficult. Jesus also said that following him involved taking up a cross. In one famous phrase, Dietrich Bonhöffer said that when Jesus calls us to follow him he bids us come and die. One biblical writer said that ‘it is a fearsome thing to fall into the hands of the living God.’

I recall one of my youth ministry heroes, Mike Yaconelli, once responding to a parent who asked for help with her wayward child: ‘Yes, I can help ruin his life.’ He meant, of course, that when someone gets involved with Jesus there is no telling where it will lead, only that it will sometimes lead in unknown paths and difficult directions. In the process, it will lead to wrestling with God.

This reality of the spiritual life is clearly pictured in several biblical passages, but perhaps most clearly in the story of Jacob wrestling with the ‘angel of the Lord’ (who in fact turns out to be none other than a manifestation of God). Jacob wrestles with God, is injured in the process, but in the end receives God’s blessing and a new name: ‘Israel’, meaning ‘God-wrestler.’ Eventually not just this one person but all God’s people in the Hebrew scriptures are called Israel—a nation of ‘God-wrestlers.’

Sadly, many young people are unprepared to meet a living God who refuses to dwell in religious boxes, no matter how pretty we try to make them—a God who is a respecter neither of ‘personal space’ nor ‘comfort zones.’ When you expect God always to lead gently like a shepherd, as God most certainly does sometimes, what do you do when this God turns dangerous and wants to wrestle?

To be sure, much of what passes for wrestling with God is not really so much about God as it is with things we think or believe or have heard about God. Sometimes all of us, young or not, confuse things we’ve been told about God with God. Sadly, too often young people are subjected to attempts at ‘discipleship by indoctrination’ and are not taught how to wrestle through issues and beliefs. As Anne Lamott puts it, in a slightly different context: ‘God forbid that you should have your own opinions or perceptions—better to have head lice.’ [Bird by Bird, 110-111]. A theology professor I had one time told me in class that ‘You will find it much easier to live with yourself if you would just stop asking questions and believe what I say.’ What he really meant was that he would find it much easier to live with me if I stopped asking questions.

The unhappy truth is that this approach to discipleship doesn’t stand young people in good stead when beliefs are challenged, either from within or without. Through years of experience working with youth, I have witnessed far too often how it sets them on a course for disillusionment and disaster. It may seem like hard work, but it is far easier to teach basic navigational skills than to rescue those who have shipwrecked.

Many youth leaders and pastors, however, find themselves ill equipped to deal with the real-life questions, fears, doubts and struggles that young people face. In part, the church is to blame for this situation because we just have not invested the time, treasure and talent we talk so much about in either our young people or those who minister most directly among them.

In another way, we have simply not awakened to the illusion that we have to have the answers—that we have to somehow ‘fix’ the beliefs and ‘counter’ the doubts and ‘reassure’ the fears of young wrestlers. As we learned the true nature of spiritual mentoring as ‘walking with someone,’ we realise that integrity means refusing to ‘play-act religion’; it means admitting that we don’t have all the answers, letting them know that we, too, are wrestlers and committing ourselves to discerning together. Wrestling with our beliefs, struggles and faith can be a lonely experience when we are left feeling like we wrestle alone. How much better to know that we are part of a community of wrestling people!

This is even more important when we are not just wrestling with things about God but actually with God. God is just not some Big Idea out there somewhere. God is not just some Star Wars Force. God is the living God, and the living God engages us in living relationships. Living relationships are not just joyful and full of easy blessing. They’re messy, sometimes difficult, and often involve wrestling with the beloved—even the Beloved. I don’t suppose it’s coincidental that the biblical writers use metaphors of friendship, family, romance and marriage to describe our relationships with God.

Many biblical heroes from Moses and Lot through the prophets wrestled with God in different ways. Even Jesus wrestled with God in prayer to the point of sweating blood. The post-biblical saints frequently describe their relationship with God in terms of a phrase I’ve chosen for my tombstone: ‘I had a lovers’ quarrel with God.’

Young people simply cannot be abandoned in their wrestling with God. Even though we can’t spare them the risk of injury in the process, what better than for them to engage our dangerous God—or to wrestle with the sense of God’s absence—in the community of other God-wrestlers?

Is it worth it? Yes, of course, because, as Mr and Mrs Beaver said of Aslan, of course God’s not safe—but God is good.

Fresh Expressions of Church among the Maasai?

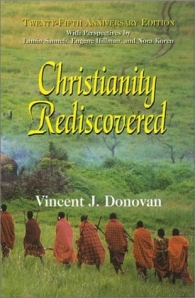

Vincent Donovan was a Catholic missionary to the Maasai in Tanzania in the 1960’s and 1970’s. His book Christianity Rediscovered (Orbis 1978) has been a best-seller ever since, and I am not the only teacher who has used it in classes on mission and evangelism to help students think through issues of Gospel and culture.

Vincent Donovan was a Catholic missionary to the Maasai in Tanzania in the 1960’s and 1970’s. His book Christianity Rediscovered (Orbis 1978) has been a best-seller ever since, and I am not the only teacher who has used it in classes on mission and evangelism to help students think through issues of Gospel and culture.

Donovan has come to prominence recently in North America through a discussion of his work in Brian McLaren’s Generous Orthodoxy (Zondervan 2004), and in Britain by being highlighted in the ground-breaking Church of England report, Mission-Shaped Church (Church House Publishing 2004).

What did Donovan do that has captured so many people’s imagination? When he got to Tanzania, missionaries had been engaged for decades in building hospitals and schools to serve the Maasai, but there were few Christian communities. He asked his bishop for permission to go and simply ask people in the Maasai villages whether they would be interested to talk with him about God. Their answer was two-fold: Who can refuse to talk about God? and Why did it take you so long to ask?

So, for a year he visited the villages each week, and they talked about God. In the process, Donovan realised how woefully inadequate his theological formation had been to deal with a front-line evangelistic situation like this. He also came to the conviction that he could not impose on the Maasai a western-style Catholic church, but that they would have to learn to “do church” in a way that authentically expressed their own culture.

You can see the attractiveness in such an approach for Western Christians trying to figure out authentic witness in a post-Christian society. Donovan addresses two of our main questions: How do we explain the Gospel to people who have no Christian background? and, What does church need to look like to serve those people in their culture? (For those of us in theological education, he raises a third question: How should we train people for pioneering ministries in this culture?)

In the past three years, I have been on something of a personal quest to find out what happened to the Maasai churches Donovan founded. (He himself died in 2000.) In the course of that quest, I have visited a priest in Tanzania who was trained by Donovan in the 1970’s and is still working among the Maasai; been with him to a mass in a remote Maasai church; visited other missionaries who worked with Donovan; and been entrusted by Donovan’s sister with the task of editing his letters home from Tanzania (due to be published by Wipf and Stock in the next year; Brian McLaren has agreed to write the foreword).

So what did happen to those churches? Briefly: things did not turn out as Donovan expected. There were three problems. For one thing, it turned out that the Maasai themselves (like many Africans) were very conservative and did not want to do church any other way than the way the missionaries themselves already did it.

As a result, the mass I went to was very traditional in form, except that it was all in Maasai. But there were touches of local culture: the priest wore black (the sacred colour of God), and had a stole embroidered with cowrie shells. He held grass, symbol of reconciliation, in his hand through the service, and blessed the people by sprinkling them with milk during the prayers. And the singing was haunting, and unlike anything else I have ever heard.

Secondly, very few Maasai have gone through the rigorous and extensive training required for Catholic ordination, and there is little provision for lay ministry except for the fine work of locally-trained itinerant Maasai catechists. This means that, once this generation of missionaries dies out (and for the most part they are now in their seventies), many of the scattered Maasai churches will likely die too.

The third problem was that the Catholic hierarchy in Tanzania had no interest in inculturation. Perhaps this is because they are still relatively new Catholics, and feel the need to prove themselves as “real” Catholics.

Thus an irony exists: that the white American missionaries have been pushing for things to be done in a Maasai way, while the Tanzanians themselves (both at the grassroots and among the hierarchy) prefer to do things in a European way.

Was Donovan’s work then simply an inspiring but naïve experiment, doomed to failure? “Failure” is a tricky word to use in the Christian life or in ministry. Just because things do not work out the way we expect does not mean that, in the economy of God, they have failed.

In the case of Donovan, the way his ideas are being picked up in North America and Britain are encouraging. In particular, the three obstacles he encountered are likely to be less in this part of the world.

- In the Fresh Expressions movement in Britain, there are certainly many non-traditional ways of being church which are attracting people with no Christian background. New people are not complaining that “this is not the way church ought to be.”

- In terms of theological education, Wycliffe College is following the lead of seminaries in Britain and moving towards training ordinands for specifically pioneering types of ordained ministry.

- And, as for bishops, my experience is that there is great openness among Canadian bishops to new forms of church and ministry. I spoke to one bishop after the Vital Church Planting conference in Februarys and asked him what he had learned. “That bishops have to be permission-givers,” he replied.

Not that Vincent Donovan is the be-all and end-all of missional ministry. He in turn was greatly affected by the writings of Anglican missiologist Roland Allen, such as Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours?(1912; Eerdmans 1990) And both of them found the example of Paul in the Book of Acts the most helpful model for what they were trying to do.

But, of course, Donovan and Allen—and Paul himself—were all inspired by the ultimate example of missional ministry: the Word of God who became flesh—and moved into the neighbourhood.

What Nick Offers

As team leader of Fresh Expressions Canada, Nick is in a unique position to provide an introduction to Fresh Expressions, which started life in England as an initiative of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York and the Methodist Council in 2004, with a brief to encourage churches all across England to establish new congregations and Christian communities through creative and innovative outreach. This was a response to the changes experienced in English society over the past fifty tears, many of which we have experienced here in Canada. Since 2008 Fresh Expressions Canada has been working “to encourage the development of fresh expressions of church alongside more traditional expressions, with the aim of seeing a more mission-shaped church take shape throughout the country.”

To date he has presented “Changing Times-an introduction to Fresh Expressions”, to the National House of Bishops, the Vision 2019 Planning Team, a theological college, General Synod 2010, and diocesan synods.

A Fresh Expression of Amnesia

If we are to become a church shaped by and for God’s mission in this world, the last thing we need is a fresh expression of amnesia. 233 variations of the word “remember” appear in Old and New Testaments. As poet and philosopher George Santayana has it, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” So as we immerse ourselves in talk of being sensitive to the multiplicity of different contexts and cultures around us in Canada, and of the need to connect appropriately with those contexts and cultures, it is salutary to be reminded that we haven’t always thought, much less acted, in this way.

If we are to become a church shaped by and for God’s mission in this world, the last thing we need is a fresh expression of amnesia. 233 variations of the word “remember” appear in Old and New Testaments. As poet and philosopher George Santayana has it, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” So as we immerse ourselves in talk of being sensitive to the multiplicity of different contexts and cultures around us in Canada, and of the need to connect appropriately with those contexts and cultures, it is salutary to be reminded that we haven’t always thought, much less acted, in this way.

The tradition goes back at least as far as Peter the apostle and the interior struggle that ensued when God presented him first with a triple vision on a rooftop in Joppa, followed closely by the very human invitation to enter the home of a Roman. The Council of Jerusalem described in Acts 15 similarly struggled with questions of what some would call contextualisation. Should we impose our way of worshipping and following Jesus on another culture, or should we help that culture develop its own response to the God who Jesus Christ reveals?

In the clash between the Celtic church and Rome in seventh century Britain over such world-shatteringly important matters as the “right” haircut for Christians and the ”right” time to celebrate the Resurrection, we see the very human tendency to try to impose “our” way (which to us is obviously the right way) on those with whom we come into contact. Of course, the tendency is made worse when we find ourselves part of a dominant and powerful group which has the ability to enforce “our way” of doing things on others.

At the same time, there has also been a recognition that God has a different view of diverse cultural expression. The miracle on the day of Pentecost was not so much that visitors to Jerusalem from throughout the Mediterranean world suddenly became able to understand Aramaic, spoken with a decidedly Galilean accent, but that these visitors had the “mighty works of God” proclaimed to them in their own native languages by people who were previously unable to speak (or presumably understand) those languages. For some strange reason, God appears to accommodate himself to different tribes, tongues and nations.

Thomas Cranmer picked up on this theme in the sixteenth century with the move in public worship from Latin into a tongue “understanded of the people.”[1] Unfortunately, many Anglicans since Cranmer seem to have forgotten this principle, and instead we have often imposed a foreign language and culture on people to whom we went bearing the gospel of Jesus Christ. (A particularly Canadian example of this would be the Residential Schools, many of which were church-run). At the same time this attitude has sometimes led to the trivialising, belittling and dismissing of forms of worship developed by the “receiving” group in their own language and culture.

A notable exception to this attitude is Robert McDonald, the nineteenth century missionary, and translator, of the Yukon:

McDonald travelled extensively, visiting native camps throughout the area. He had a natural empathy and respect for their culture and concerned himself with teaching them to read in their own language so they would have access to the teachings of the Bible during his absences. Two years after his arrival at Fort Yukon, he baptized the first Gwitch’in converts. Over the course of his 42 years in the North, he baptized 2,000 adults and children.[2]

The confluence of First Nations people with the Christian faith has produced some distinctively First Nations expressions of the faith. One example is the continuing American Indian hymn sing tradition, in which people gather towards dusk for a communal meal, followed by story telling and hymn singing which could continue far into the night. Bishop Mark McDonald tells us these have often been looked at by some white Christian leaders as being inferior or inappropriate expressions. This propensity to judge one cultural expression of Christianity by the standards and through the lens of another is a danger that will need to be avoided if fresh expressions of church in all cultures and contexts are to flourish and to receive the respect which they deserve.

The apostle Paul offers us this model for a different way of proceeding.

Think of yourselves the way Christ Jesus thought of himself. He had equal status with God but didn’t think so much of himself that he had to cling to the advantages of that status no matter what. Not at all. When the time came, he set aside the privileges of deity and took on the status of a slave, became human! Having become human, he stayed human. It was an incredibly humbling process.[3]

We are being offered the exciting opportunity of engaging with God’s mission in a post Christendom context, but this will only be realized fully if we have the courage to face the mistakes of the past, taking appropriate responsibility for them, and taking great care not to repeat them.

[1] Article 24 of the Church of England [2] http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/BishopStringer/english/mission-mcdonald.html [3] Philippians 2:5-7 (The Message)

Can Stingy Churches Be Missional Congregations?

I’m watching as the pastor in a megachurch prepares to receive the Sunday offering. This is a “prosperity” church where you have only to claim your pile of riches on Sunday to receive it on Monday-where being a consumer is not a systemic evil but a divine right.

I’m watching as the pastor in a megachurch prepares to receive the Sunday offering. This is a “prosperity” church where you have only to claim your pile of riches on Sunday to receive it on Monday-where being a consumer is not a systemic evil but a divine right.

Food for judgment. But a lifelong missionary, now a member, says to me, “This is the most generous church I have ever been in!” I’m watching for it. The pastor speaks. He says three things. First, “prosperity” is not luxury but having more than you need. Second, for believers our true wealth lies in our relationship with God, even when material blessings slip through our fingers.

Third, he reminds that the economy has brought hard times to many. Then he asks us to take a second envelope from the pew rack, insert money or a cheque, then give it to someone who is in need. I wonder how many people follow through.

Upon reflection, I see in this moment of offering first, the total comfort of the pastor to talk about money; and second, the total acceptance of the people to hear it, and to respond. I am transported back to my own childhood in the Pentecostal church where money is seamlessly interwoven with praise, preaching and piety. At the age of 15, I give my eighty cents tithe on a monthly government Family Allowance cheque of $8. What is happening in this middle class megachurch is in a way not so different from my rural Maritime church-whether poor or wealthy, we honour God with the first fruits of our labour, and God will supply our needs.

My eventual leap into the Anglican family was thick with cultural difference, including attitudes to money. I soon realized that money was a deeply private matter, mentioned perfunctorily once a year at “pledge time,” and giving was measured carefully to just meet the budget presented by the finance committee. The “biblical tithe” was seldom mentioned, and “tithes and offerings” was as unfamiliar as hillbilly music in a cathedral, and just about as unwelcome. Of course there were stellar exceptions, but that is the point-they were exceptions.

It took me years to realize the impact of church culture. Culture is the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that say in effect, “this is who we are” and “this is how we do things.” Desired change in either one cannot be achieved by mounting interesting programs alone. Programs are an important delivery system, but cannot by themselves change the culture of a congregation.

Back to money and church. What I encountered in my new church family was a cultural phenomenon of middle class North America. As long ago as 1929, H. Richard Niebuhr named it-I was now part of “a bourgeoisie whose conflicts are over and which has passed into the quiet waters of assured income” [cited in Durall, 45]. The effect of these “quiet waters” is predictable and discernible. Our money is ours, not yours or even God’s. We give as we choose, not out of duty, compulsion or imposed scale. We are offended by money talk outside the liturgical rhythm of the fall pledge drive, like the woman in my former congregation who was upset when I preached a sermon on money in June instead of October.

Of course there is more money talk these days because we are a shrinking and aging church in the midst of mounting maintenance costs for equally aging buildings. There is an increasing urgency on the part of leaders who are aware of our mainline culture, and some are finally ready to give up some of our entrenched practices which seem like debilitating cultural baggage.

Now to our question-does this stingy and measured attitude to money hinder a congregation from being missional? To put it differently, can a congregation be truly missional without being generous? My preliminary conclusion is that it may be possible, but it is likely as difficult as getting a camel through the eye of a needle.

Two fundamental reasons for the difficulty come to mind. As already mentioned, mainline Christians are mostly rather secure middle-class folk. The older generation is particularly committed to our cultural institutions, while the younger generation is more personally and consumer motivated. This is not a critique of middle class Canada (I am part of it, after all) but is intended to point out how this cultural status affects our attitude to money. The second reason is that the older generation, which warms most of our pews and gives the most money, responds best to the needs of the institution. For them it is hard to give beyond the needs displayed on the annual income-expense pie chart. Patterns of giving that stretch far beyond church upkeep are understandably difficult.

A missional church will call forth much more from its members than is currently expected or received in most of our mainline congregations, and at every level. But in order to achieve these changes, the culture of the congregation must be changed. We need generous congregations that will embody the character and spirit necessary to respond to the larger challenge of the gospel.

I have no magic wand, and consider myself to have been only partly successful in accomplishing this goal in my own parish ministry. But the following guidelines may serve as preliminary pointers, if not a detailed map, for moving forward.

1. Make every effort to break through the cultural glass ceiling of silence regarding money. This will take more courage than most of our pastors have the stomach for. It will require finding creative and effective ways to incorporate the subject of money in sermons, teaching, and decision-making processes. It will call for involving more laity who share your views.

2. Address the spiritual benefits of giving, not just the moral “ought.” This is a challenge because many of our pastors (1) do not believe in tithing as a New Testament principle, (2) are unconvinced that there is a “spiritual law” of giving, and (3) do not think that there is any connection between generous giving and an enriching personal faith.

3. Shun the dichotomy (spiritual apartheid?) between those with more of the world’s goods and the materially poor. Jesus made a stunning observation for the religious leaders in the synagogue when the widow gave her last penny. Rather than rushing to protect her from her recklessness, he praised her example of sacrificial generosity-not to mention the stinging blow he dealt to the hypocritical onlookers. To deprive the poor of the blessing of giving is to score a moral and spiritual indignity upon them.

4. Preach and teach both the macro and the micro dimensions of giving. That is, preaching macro would include the belief that (1) all that we are and have belongs ultimately to God, who provides the good things of life on loan, and (2) giving is one of God’s ways of employing his followers in the world. We give generously for evangelism because we believe that every person deserves to know God’s gracious offer of salvation and fullness of life in Jesus. And we give for the alleviation of pain and poverty in this world because we know that our resources and ministry are God’s way of giving witness to a new world. In other words, biblical generosity means sharing the Good News as well as our resources.

Preaching micro is making the message relevant and real in your own congregation. The best of preaching motivationally will address both head and heart. What would it take to create such a climate of generosity in our churches that people would find it hard to keep their hands off their wallets when a Kingdom vision is cast? What would it take to bring our message home with the kind of excitement described by one visitor to a 10,000 member megachurch: “a cup of designer coffee with lightning bolts coming out of it” [Durall, 26]? Our calling is to help people see that giving generously for God’s work is not only right but desirable.

5. Work with the symbiotic relationship between giving to God and giving missionally. Research shows that just giving to worthwhile outreach projects does not create a culture of generous giving. We first seek to form disciples who live out the truth that everything we have belongs to God. But opportunities to give are important means by which we grasp the reality and blessing that comes from giving.

6. Do not be afraid to appeal for sacrificial giving. Our consumer culture is not accustomed to depriving itself of its wants. But for Kingdom purposes, the decision to delay trading in the family car or postponing a kitchen renovation becomes a moment for weighing the sacrifice factor. As Bill Hybels says, be bold in asking for money, since most will likely end up spending it on frivolous things anyway.

7. Enlist laity in the culture change. Observe those lay persons who already show signs of a generous spirit. Do not limit yourself to those who have more money to give. Find ways to raise their visibility in the congregation. Give them opportunities to share their testimony, especially the ways God has blessed them. Ask elected leaders (wardens and church board) to lead by example-commit to tithing or have a plan to work toward it through increased proportional giving.

Churches are never just about bricks and mortar. They are either weekly comfort stations for passive believers, or they are hospitals for the sick, redemptive centres for the sinner, and launching platforms for sharing God’s good news from the neighbourhood to the farthest continent. The former takes only a little money to keep the doors open. The latter is secured by a divine purpose, a global vision and lots of money. Whether or not we feel the pain of the sacrifice depends entirely upon the angle of vision and disposition of the heart. Miracles are not always instantaneous. This one will take a minimum of five years.

REFERENCE

Michael Durall, Creating Congregations of Generous People (Washington, DC: Alban Institute, 1999.

Natural Church Development is…Still Developing

Many of us were introduced to NCD as a “survey” that evaluated 8 key ministry areas: leadership, ministry, spirituality, structures, worship, small groups, evangelism, and relationships. 60,000 surveys worldwide have demonstrated the validity of NCD’s initial premise: thriving churches have a similar approach. In healthy churches leadership is empowering, ministry is aligned with spiritual giftings, structures function well, spirituality impassions and guides the rest of life, God inspires in the worship, the whole person is engaged through small groups, evangelism relates to the needs of those beyond the church, and relationships within the parish have a loving quality. The tragedy has been that many parishes have “done a survey” or two and moved on to something else.

While the newly updated survey is still extremely useful for helping parishes diagnose health issues, the process has evolved beyond getting the numbers and attempting to improve the weakest link. Some parishes were able to take the survey results and improve them, but many struggled with the pragmatic reality of implementation.

Bill Bickle, an Anglican layman, management consultant and the new international liaison for NCD in Canada has some good news for parishes struggling to translate analysis into action. He says, “Change has evolved in three key areas. When the Canadian Church adopted NCD in 1999 it was heavily influenced by the big box model of churches south of the border. Parishes used it as a program to boost numbers. I’ve met dozens of people who’ve told me ‘We tried NCD once, and then moved on. . . .’

Bill Bickle, an Anglican layman, management consultant and the new international liaison for NCD in Canada has some good news for parishes struggling to translate analysis into action. He says, “Change has evolved in three key areas. When the Canadian Church adopted NCD in 1999 it was heavily influenced by the big box model of churches south of the border. Parishes used it as a program to boost numbers. I’ve met dozens of people who’ve told me ‘We tried NCD once, and then moved on. . . .’

“We’ve rediscovered a deceptively simple Cycle of gathering information, understanding it deeply, and putting a plan of action into place. A five year old uses the same process figuring out a new route to school. It is deeply imbedded into our everyday processes already, which makes it a natural for parish that doesn’t know what to do next.”

The Cycle is a lifestyle pattern for parishes. After doing the survey, time is spent trying to understand why the results are what they are. A plan is developed out of that understanding, and applied. As the plan is applied the parish pays attention to what they are experiencing and perceiving; whether or not some measure of transformation is underway. A parish might ask if God is guiding them in some area. After a year or eighteen months perceptions are put to the test through another survey, and the cycle begins again.

What makes this process much easier to implement now is a new detailed analysis of how survey respondents answered each survey question, within each category. Called “Profile Plus,” a parish can identify the 10 most vibrant strands of its internal life – across ministry categories – and also the 10 weakest. It is here interesting patterns emerge. A parish may score extremely high on Loving Relationships but find a lowest score for the entire survey is hidden within that category. For instance the survey question asking, “I know of people in our church with bitterness toward others,” could be dampening the experience of God in worship and stifling small group life. It could affect the functioning of Parish Council, hinder evangelism, and create an environment where leaders exercise tighter control. We all know intuitively that there are issues behind the issues that are difficult to identify.

Many parishes tend to get stuck somewhere in the process. They may gather information and jump to action before taking time to reflect on what the information means, or plan without putting into action, or fail to evaluate whether the plan has produced desired results by taking a new survey. The Cycle encourages the doers to slow down and think, the thinkers to speed up and do, and provides a quantified evaluation at the end to launch the next cycle. When a parish has undergone the entire Cycle several times, hidden or undiscussed issues emerge and there is possibility for deep transformational change. We can plan for what we understand. We can experience God’s grace as we work it out. We can gauge whether our efforts have borne fruit and begin again.

One other insight has emerged over the last 10 years, that the spread between highest and lowest scores is significant. If a church is extremely developed in one area and extremely undeveloped in another, there is an instability within that needs to be addressed more urgently than simply bringing up the numbers. A weak athlete with two legs of equal length will respond to training more readily than an athlete with a highly toned right leg, and a left leg half a meter shorter. The gap between strongest characteristic and lowest must be narrowed. It’s not simply a matter of attaining a higher score.

Parish ministry is increasingly challenging in post-Christendom. NCD is a post-Christendom tool which resonates with European and Canadian experience, is parish friendly – and most importantly – relates the task of Church to the work of God in understanding, in action, and in experience.

Churches wishing to learn more about the suitability for NCD in their context should contact Bill Bickle at NCD-Canada@fordelm.com . An “NCD Primer” can be downloaded at www.ncdcanada.com . Churches that did NCD under the former system may wish to try again, using Profile Plus. The NCD Cycle Manual can now be downloaded from the same website, left hand column.