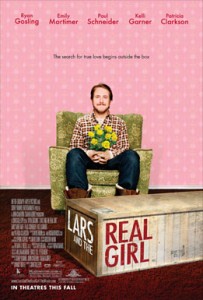

Earlier this past summer, my wife and I watched Lars and the Real Girl starring Ryan Gosling. If you’re a fan of the HBO series Six Feet Under, you’ll really enjoy this one. The screenplay was written by Nancy Oliver who wrote some of the best Six Feet Under episodes. Not only is this movie fall-off-your-chair funny (which I did when Lars introduces his family to Bianca), but it’s also a sociopolitical commentary on how society deals with emotional and mental health. I won’t get into the plot too much, but the story is about a delusional breakdown of the main character, Lars (played by Gosling) who has been unable to deal effectively with past family tragedy (the loss of his mother, occasioned by his own birth, and the loss of his father when he was a young boy). Clinically, he would be labeled with something like social anxiety disorder. Lars has repressed his emotions to such a degree that even the touch of another person causes him pain (“the kind of pain when your feet get really cold then you come into a warm house and they burn…it feels just like that”, Lars tells us). He ends up ordering a ‘real doll’ from a website and begins a delusional relationship with her and the rest of the story deals with how his family and his community (his church, workplace, friends, his therapist, and a really real girl) support him and help him through his delusion.

Earlier this past summer, my wife and I watched Lars and the Real Girl starring Ryan Gosling. If you’re a fan of the HBO series Six Feet Under, you’ll really enjoy this one. The screenplay was written by Nancy Oliver who wrote some of the best Six Feet Under episodes. Not only is this movie fall-off-your-chair funny (which I did when Lars introduces his family to Bianca), but it’s also a sociopolitical commentary on how society deals with emotional and mental health. I won’t get into the plot too much, but the story is about a delusional breakdown of the main character, Lars (played by Gosling) who has been unable to deal effectively with past family tragedy (the loss of his mother, occasioned by his own birth, and the loss of his father when he was a young boy). Clinically, he would be labeled with something like social anxiety disorder. Lars has repressed his emotions to such a degree that even the touch of another person causes him pain (“the kind of pain when your feet get really cold then you come into a warm house and they burn…it feels just like that”, Lars tells us). He ends up ordering a ‘real doll’ from a website and begins a delusional relationship with her and the rest of the story deals with how his family and his community (his church, workplace, friends, his therapist, and a really real girl) support him and help him through his delusion.

Lately, I’ve also been reading Michel Foucault’s History of Madness and early on, Foucault talks at length about leprosy and how medieval Europe, especially the church, shunned and relegated all lepers to the outside of the city gates (a scapegoating role the mentally ill-the mad-would come to fulfill after leprosy disappeared from Europe).

This liturgy of exclusion would carry over into the eighteenth century as society became less and less hospitable to madness, controlling it by labeling it, corralling it, and ‘solving’ it with institutions and the systematic treatment of ‘unreason’.

What struck me in this movie, is how Lars’ family and community (yes, even his church!) came alongside him and didn’t expel him or scapegoat him. However, the most compelling aspect, in my opinion, is how the therapist works with Lars. We never get the sense that she’s treating a problem. In one scene, Lars’ brother wants an answer, he wants a solution to this problem as quickly as possible. The therapist tells him, in probably the most subversive scene of the film, that this delusion isn’t a problem, in fact, it can be a gift for Lars and for those around him, which in fact, it turns out to be.

Now, I realize that labeling this delusion ‘a gift’, especially for those who have lived through or live with mental health issues, is a tenuous description but one that is, at least here, quite apt. In fact this ‘gift’ has its own dignity-Lars is allowed to live in a community without being ‘powered’ over, without being confined and expelled from society. As St. Paul tells us, “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise”. In the end, Lars reminds us of those unsuspecting Christ-like figures like Dostoyevsky’s idiot who, in shaming the wise (or here, the healthy), actually become their salvation.

Now, I realize that labeling this delusion ‘a gift’, especially for those who have lived through or live with mental health issues, is a tenuous description but one that is, at least here, quite apt. In fact this ‘gift’ has its own dignity-Lars is allowed to live in a community without being ‘powered’ over, without being confined and expelled from society. As St. Paul tells us, “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise”. In the end, Lars reminds us of those unsuspecting Christ-like figures like Dostoyevsky’s idiot who, in shaming the wise (or here, the healthy), actually become their salvation.

The church is often shamed by these fringe figures and it desperately needs to discover how to behave like Lars’ community, learning to live with and even within the delusions of life. If we can learn that, we can also learn how to accept the gift of difference that mental and emotional health issues bring with them into our communities and so bear witness to salvation, our own included.

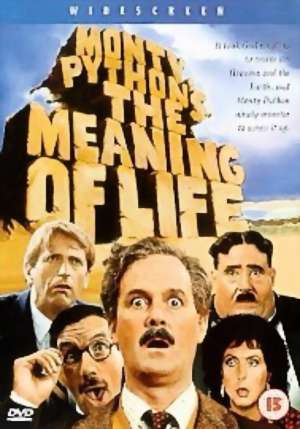

1. Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life

1. Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life 2. Douglas Adams

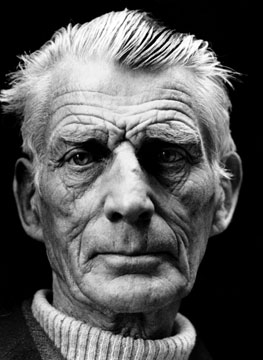

2. Douglas Adams 3. Samuel Beckett

3. Samuel Beckett 4. The X-Box

4. The X-Box Jesus

Jesus The image of God we carry around in our head is one of the most important things about us. Accurate and inaccurate images of God can lead to very different conclusions. For instance, many people have the image of God as very religious. But, from the teaching of Jesus at least, that is a pretty inadequate image. For one thing, the God Jesus believed in is the creator of all of life—not just the religious dimension of it.

The image of God we carry around in our head is one of the most important things about us. Accurate and inaccurate images of God can lead to very different conclusions. For instance, many people have the image of God as very religious. But, from the teaching of Jesus at least, that is a pretty inadequate image. For one thing, the God Jesus believed in is the creator of all of life—not just the religious dimension of it. Stories are amazing things. Some of them crop up in every culture in every century. Sometimes they turn up in different forms, but still with a recognizable family likeness. There seems to be something about certain stories that appeals very deeply to the human race.

Stories are amazing things. Some of them crop up in every culture in every century. Sometimes they turn up in different forms, but still with a recognizable family likeness. There seems to be something about certain stories that appeals very deeply to the human race. Movies are a place where the spiritual concerns of our culture often intersect with the Gospel. John van Sloten has become well-known in Calgary and around the world for “preaching from the culture.” Here he offers a sermon which analyses a popular current movie in the light of the Christian message.

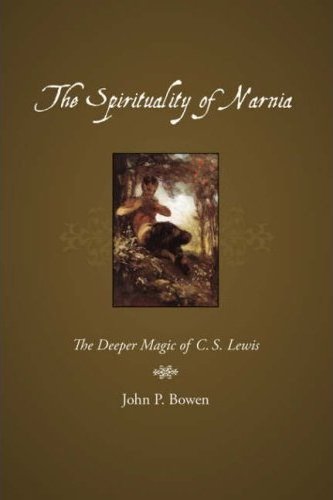

Movies are a place where the spiritual concerns of our culture often intersect with the Gospel. John van Sloten has become well-known in Calgary and around the world for “preaching from the culture.” Here he offers a sermon which analyses a popular current movie in the light of the Christian message. C.S.Lewis is one of the most unlikely children’s authors you could ever meet. He was an academic all of his life, teaching first at Oxford and later at Cambridge. He was not married till he was over fifty, and had no children of his own, nor any nephews or nieces. His closest friends were other male academics. He traveled outside the British Isles only twice: when he fought in France during the First World War and when he went on holiday to Greece towards the end of his life. And he dressed like a typical absent-minded professor, “in baggy flannel trousers and tweed jackets” and a shapeless hat.

C.S.Lewis is one of the most unlikely children’s authors you could ever meet. He was an academic all of his life, teaching first at Oxford and later at Cambridge. He was not married till he was over fifty, and had no children of his own, nor any nephews or nieces. His closest friends were other male academics. He traveled outside the British Isles only twice: when he fought in France during the First World War and when he went on holiday to Greece towards the end of his life. And he dressed like a typical absent-minded professor, “in baggy flannel trousers and tweed jackets” and a shapeless hat. I do not think the God of Christianity is particularly religious. If Jesus is right, God created all of life, not just the narrowly religious bits. So if God is interested in us, God doesn’t have to wait till we get religious. God can communicate with us many ways—through friends, books, school, experiences . . . and even movies. Movies often touch us in deep ways—and whenever we are touched deeply, that may be a signal that God is trying to get through to us.

I do not think the God of Christianity is particularly religious. If Jesus is right, God created all of life, not just the narrowly religious bits. So if God is interested in us, God doesn’t have to wait till we get religious. God can communicate with us many ways—through friends, books, school, experiences . . . and even movies. Movies often touch us in deep ways—and whenever we are touched deeply, that may be a signal that God is trying to get through to us.