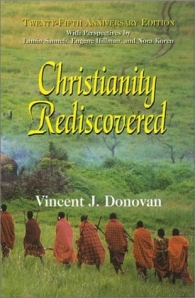

Vincent Donovan was a Catholic missionary to the Maasai in Tanzania in the 1960’s and 1970’s. His book Christianity Rediscovered (Orbis 1978) has been a best-seller ever since, and I am not the only teacher who has used it in classes on mission and evangelism to help students think through issues of Gospel and culture.

Vincent Donovan was a Catholic missionary to the Maasai in Tanzania in the 1960’s and 1970’s. His book Christianity Rediscovered (Orbis 1978) has been a best-seller ever since, and I am not the only teacher who has used it in classes on mission and evangelism to help students think through issues of Gospel and culture.

Donovan has come to prominence recently in North America through a discussion of his work in Brian McLaren’s Generous Orthodoxy (Zondervan 2004), and in Britain by being highlighted in the ground-breaking Church of England report, Mission-Shaped Church (Church House Publishing 2004).

What did Donovan do that has captured so many people’s imagination? When he got to Tanzania, missionaries had been engaged for decades in building hospitals and schools to serve the Maasai, but there were few Christian communities. He asked his bishop for permission to go and simply ask people in the Maasai villages whether they would be interested to talk with him about God. Their answer was two-fold: Who can refuse to talk about God? and Why did it take you so long to ask?

So, for a year he visited the villages each week, and they talked about God. In the process, Donovan realised how woefully inadequate his theological formation had been to deal with a front-line evangelistic situation like this. He also came to the conviction that he could not impose on the Maasai a western-style Catholic church, but that they would have to learn to “do church” in a way that authentically expressed their own culture.

You can see the attractiveness in such an approach for Western Christians trying to figure out authentic witness in a post-Christian society. Donovan addresses two of our main questions: How do we explain the Gospel to people who have no Christian background? and, What does church need to look like to serve those people in their culture? (For those of us in theological education, he raises a third question: How should we train people for pioneering ministries in this culture?)

In the past three years, I have been on something of a personal quest to find out what happened to the Maasai churches Donovan founded. (He himself died in 2000.) In the course of that quest, I have visited a priest in Tanzania who was trained by Donovan in the 1970’s and is still working among the Maasai; been with him to a mass in a remote Maasai church; visited other missionaries who worked with Donovan; and been entrusted by Donovan’s sister with the task of editing his letters home from Tanzania (due to be published by Wipf and Stock in the next year; Brian McLaren has agreed to write the foreword).

So what did happen to those churches? Briefly: things did not turn out as Donovan expected. There were three problems. For one thing, it turned out that the Maasai themselves (like many Africans) were very conservative and did not want to do church any other way than the way the missionaries themselves already did it.

As a result, the mass I went to was very traditional in form, except that it was all in Maasai. But there were touches of local culture: the priest wore black (the sacred colour of God), and had a stole embroidered with cowrie shells. He held grass, symbol of reconciliation, in his hand through the service, and blessed the people by sprinkling them with milk during the prayers. And the singing was haunting, and unlike anything else I have ever heard.

Secondly, very few Maasai have gone through the rigorous and extensive training required for Catholic ordination, and there is little provision for lay ministry except for the fine work of locally-trained itinerant Maasai catechists. This means that, once this generation of missionaries dies out (and for the most part they are now in their seventies), many of the scattered Maasai churches will likely die too.

The third problem was that the Catholic hierarchy in Tanzania had no interest in inculturation. Perhaps this is because they are still relatively new Catholics, and feel the need to prove themselves as “real” Catholics.

Thus an irony exists: that the white American missionaries have been pushing for things to be done in a Maasai way, while the Tanzanians themselves (both at the grassroots and among the hierarchy) prefer to do things in a European way.

Was Donovan’s work then simply an inspiring but naïve experiment, doomed to failure? “Failure” is a tricky word to use in the Christian life or in ministry. Just because things do not work out the way we expect does not mean that, in the economy of God, they have failed.

In the case of Donovan, the way his ideas are being picked up in North America and Britain are encouraging. In particular, the three obstacles he encountered are likely to be less in this part of the world.

- In the Fresh Expressions movement in Britain, there are certainly many non-traditional ways of being church which are attracting people with no Christian background. New people are not complaining that “this is not the way church ought to be.”

- In terms of theological education, Wycliffe College is following the lead of seminaries in Britain and moving towards training ordinands for specifically pioneering types of ordained ministry.

- And, as for bishops, my experience is that there is great openness among Canadian bishops to new forms of church and ministry. I spoke to one bishop after the Vital Church Planting conference in Februarys and asked him what he had learned. “That bishops have to be permission-givers,” he replied.

Not that Vincent Donovan is the be-all and end-all of missional ministry. He in turn was greatly affected by the writings of Anglican missiologist Roland Allen, such as Missionary Methods: St. Paul’s or Ours?(1912; Eerdmans 1990) And both of them found the example of Paul in the Book of Acts the most helpful model for what they were trying to do.

But, of course, Donovan and Allen—and Paul himself—were all inspired by the ultimate example of missional ministry: the Word of God who became flesh—and moved into the neighbourhood.

[…] Fresh Expressions of Church Among the Maasai?: John Bowen points his readers to Christianity Rediscovered, a book by Vincent Donovan and updates the outcomes, wondering, “Was Donovan’s work then simply an inspiring but naïve experiment, doomed to failure?” […]