Quick: name three movies with central characters who are fine Christians. Hmm, that’s what I thought.

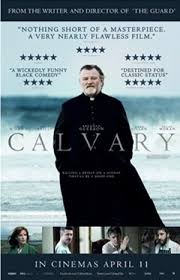

Of course, there are some— Chariots of Fire (1981), The Mission (1986), Babette’s Feast (1987), Romero (1989), Cry the Beloved Country (1995) Dead Man Walking (1995), Amazing Grace (2006), and Of Gods and Men (2010) spring to mind immediately. Even if you have more than that on your list, you probably have enough fingers to spare to add another: Calvary (2014), starting Brendan Gleeson (remember Mad-Eye Moody in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows?).

Gleeson plays a Roman Catholic priest in rural Ireland (the scenery is breath-taking—almost another  character in the film). The movie begins with one of the most dramatic openings in the history of cinema. (I could be wrong about that—there are a million movies I haven’t seen—but I somehow doubt it.) Quite rightly, the trailer features the opening scene. You can find it online. In it, the priest is sitting in the confessional, waiting for penitents. A man enters (though we never see him) but, instead of confessing, he informs the priest that he is going to kill him, and that he will do it a week from Sunday. The killing will be revenge for the sexual abuse the man suffered as a child at the hands of a priest now dead. And he chooses Father James for the simple reason that he is . . . a good priest.

character in the film). The movie begins with one of the most dramatic openings in the history of cinema. (I could be wrong about that—there are a million movies I haven’t seen—but I somehow doubt it.) Quite rightly, the trailer features the opening scene. You can find it online. In it, the priest is sitting in the confessional, waiting for penitents. A man enters (though we never see him) but, instead of confessing, he informs the priest that he is going to kill him, and that he will do it a week from Sunday. The killing will be revenge for the sexual abuse the man suffered as a child at the hands of a priest now dead. And he chooses Father James for the simple reason that he is . . . a good priest.

The rest of the movie goes through the days of that week one by one, showing the priest going about his pastoral duties—confronting, comforting, serving, counselling, visiting the pub, arguing with the village atheist, administering last rites, and leading worship. Little by little, the tension grows as Sunday draws near. (Do not go unless you are feeling strong. To say the movie is intense is an understatement. Thank God for the rough and ready humour that punctuates the script.) And the ending is, well, stunning—and abrupt. (Two people laughed at that point the night I saw it. I guess they didn’t get it.)

Father James is a Christ-like character. There are even echoes of the clearing of the temple and the scourging. Yet he is also deeply fallible. He has a troubled relationship with his daughter (he wasn’t ordained until his wife died), he has a problem with alcohol, he has doubts, and he has a violent temper. And yet, and yet.

As a meditation on the Christian life, on being a witness, on what it means to serve Christ in life and in the shadow of death, to be aware of one’s fallennness and God’s grace, it doesn’t get any better than this. Too bad Calvary won’t get any Oscars. It deserves them.