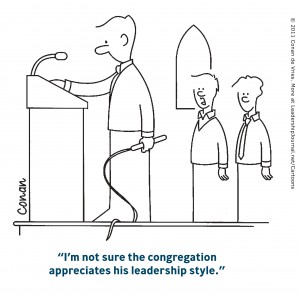

Leadership comes in many shapes and sizes—not just one. And different situations call for different styles of leadership. So what types of leader does the church need right now?

Clichés become clichés for a reason—usually because they are true. So I am going to risk saying that because the church is in crisis, we need a different kind of leader from those we needed fifty years ago. It is a cliché—but it is also true.

I was thinking about this recently when speaking at the induction of a friend, Ross Lockhart, as Director of Ministry Leadership and Education at St. Andrew’s Hall, the Presbyterian College at the Vancouver School of Ministry. My brief was to “give the charge.” This was not a phrase I was familiar with, so I asked Ross whether it meant I had to tell everyone how wonderful he is, or whether it was a chance for me to tell him what to do. Modest man that he is, he said the latter. I was happy to oblige—though I would happily have done the first too.

Since seminaries like St Andrew’s are in the business of training leaders, and since Ross is teaching leadership, it seemed like a good opportunity to reflect on what kind of leaders the church needs in today’s world.

I suggested there are four kinds of leader we need:

- The traditional pastor

Traditional healthy churches need leaders who can preach and teach, train and give pastoral care, lead inspiring worship, and be competent administrators. It is a tall order, but over the years, even centuries, many have done this wonderfully well. And seminaries continue to turn out good shepherds of this kind.

Frankly, however, there is a limited need for those with this skill-set. This kind of pastoring assumes that the congregations to which they go are in healthy midlife, and simply need building up and encouraging in the way they are already going. But, sadly, there are not many of those around.

It is true, of course, that a good traditional pastor may be able to win back the lapsed and get them energised again. That is a much-needed contribution to the work of the Kingdom, since the “dechurched” are still a significant portion of the Canadian population.

But the dechurched are a limited market. It is those who have never had a church experience—the unchurched—that is the fastest-growing demographic (the “nones,” as they are often called), particularly among the young. So if traditional pastors are the only kind of leader we are producing, soon there will be nobody left for them to pastor.

- The palliative care leader

Many churches will not survive the next ten years—in some cases the next five years. What kind of leadership do they need?

In my Doctor of Ministry cohort some years ago was a woman who, with her husband, was pastoring a small ethnic congregation, originally from central Europe, in a small town in the Niagara Peninsula. The young people were long gone, and the community of those who still spoke their mother tongue was shrinking. Humanly speaking, there was no way that congregation would ever grow. The pastor told me, “My husband and I feel called to minister to this congregation until the last person dies.”

I have the utmost respect for that kind of calling—one I am sure I could never fulfil myself—and the need for “congregational palliative care” is both crucial and growing. Congregations die all the time—just as (please God) new churches are born all the time—but to help them die with dignity and even joy is crucial. God loves these people, after all, and they have often served God faithfully for long decades, through thick and thin. There are too many stories of how such churches have been “closed” with needless clumsiness and lasting hurt.

Where are the palliative care pastors such situations need? And who is training them?

- The turnaround leader

The third is perhaps the most difficult of the four models of leader: the one who can help moribund congregations change from looking after their existing members to understanding that they are called to participate in the mission of God.

Why is this difficult? Well, for one reason, the changes required are pretty fundamental, in all likelihood involving their grasp of the Gospel, their understanding of church, their long-standing ministry habits, and (not least) their theology.

Twenty years ago, I thought in my naivety that most struggling congregations would be willing and even excited to make this kind of change in order to thrive again: all they needed was to know how, and good leadership to help them do it.

Now we know that is not the case. Given the choice between changing and dying, many will weigh the options: change? death? Hmmm . . . and then choose death as the easier choice. Why is it easy? Because all they have to do is keep doing what they have always done.

The other reason this has proved difficult is that most “traditional pastors,” however much they might want to bring about change, simply do not know how. It requires a different skill-set. For a pastor to try to bring about that kind of change without the requisite gifts, and in the face of the inevitable resistance, is a recipe for conflict and sometimes burnout.

Of course, there are some congregations who will choose the painful road of change. They need leaders with clear vision and thick skins and stick-to-it-ivenes—not to mention lots of love—to guide them through the transition. These are the turn-around pastors.

- The pioneer leader

Finally—and maybe in the long run most important—we have a need for leaders who can start new Christian communities (often called fresh expressions of church) in contexts where existing churches can never go: new churches which reflect the culture of their context, and which have mission in their DNA from day one.

What kind of leader can do this? One who is unusually gifted in evangelism, who is as comfortable in secular culture as in church culture, who has experience of pulling innovative teams together, who has a track record of starting things, and has a competent grasp of orthodox theology. (The last is particularly important for church planting teams because, in the new situation, they will be the sole “bearers of the tradition”!)

In many cases, we will need to recruit such people, rather than waiting for them to come to us. Often the young people who come up through our churches’ farm system know little apart from life in the traditional congregations they come from, and which have recognised that they have gifts for . . . traditional ministry.

But the kind of people who are gifted to pioneer new congregations have in many cases never considered ordination because their image of ministry leadership is the traditional one, and they know that is not for them. We need to persuade them that they are exactly what the church needs these days—and train them appropriately.

Why does this matter?

After all this, we need to remember why these things are important. The need for suitable leaders is not in the first place about the church or leadership, or teaching and training. At the heart of all this concern is the Gospel of God—the good news of Jesus. After all, it is the Gospel that brings the church into being (if there were no Gospel, there would be no church), it is the Gospel that gives shape to what we mean by leadership, and it is the Gospel that directs our understanding of mission.