A professor and writer shares his summer reading list

Summer for me always means more time to read. Whether on the deck, with a cup of tea in hand, or at a  friend’s cottage, looking out at the lake, or simply in bed at night when I don’t have to get up early the next day, reading is one of life’s great pleasures. The difficulty is always deciding what to read. There is so much to choose from. But fiction is always at the top of my list.

friend’s cottage, looking out at the lake, or simply in bed at night when I don’t have to get up early the next day, reading is one of life’s great pleasures. The difficulty is always deciding what to read. There is so much to choose from. But fiction is always at the top of my list.

For one thing, I love detective stories: Agatha Christie, P. D. James, Ruth Rendell, Margery Allingham, Dorothy Sayers (why do so many women write detective fiction, I wonder?). The attraction for me is not so much the violence (which I could usually do without), as the foretaste they offer of redemption—by the end, evil, however dastardly or subtle, has always been found out and justice has been done. In everyday life, we seldom see this so clearly, as any day of watching the news will remind us.

Detective fiction is a good reminder that, in the end, God will conquer all evil and, in the most ultimate sense possible, “all manner of things shall be well.” So, detective fiction is always part of my summer reading.

I have also been trying to follow C.S.Lewis’ advice that good books, especially old books, should be read more than once. Here he is on re-reading books: “An unliterary man may be defined as one who reads books only once.” And on the value of old books: “If one has to choose between reading the new books and reading the old, one must choose the old: not because they are necessarily better but because they contain precisely those truths of which our age is neglectful.”

Current bestsellers often disappoint. Lewis would not be surprised.

Although they are probably not all what Lewis meant by “old,” in the past year or two, I have re-read The Mill on the Floss (George Eliot, 1860), Brave New World (Aldous Huxley, 1931), The Plague (Albert Camus 1947), The Chosen (Chaim Potok, 1967), and Watership Down (Richard Adams, 1972).

Every one of them was worth the time.

I am currently working on Moby Dick (Hermann Melville, 1851), and realizing much more of where Melville is coming from, religiously and philosophically, than I did last time I read it, when I was 16.

Again, Lewis is right: “The re-reader is looking not for actual surprises (which can come only once) but for a certain ideal surprisingness. . . . We do not enjoy a story fully at the first reading.” On my list of old books to read and re-read, I have still have Dickens, Hardy, Swift, Fielding, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and others to (re)discover. I will obviously need a lot of summers.

I have also tried to plug some of the shameful gaps in my reading. How did I ever miss The Moon and Sixpence (Somerset Maugham, 1919) or The Great Gatsby, (Scott Fitzgerald, 1925), for instance? I have also got quite involved in the Victorian novels of Anthony Trollope, particularly The Chronicles of Barsetshire (e.g. The Warden, 1855; Barchester Towers, 1857; and The Last Chronicle of Barset, 1867). If you ever wonder what people mean when they refer to “Christendom,” there could be no more vivid depiction of it, with its strengths and weaknesses, than this portrait of the Anglican world of 19th century England. Oh, and the movie, The Barchester Chronicles (1982), made Alan Rickman famous, with his portrayal of the obnoxious low-church clergyman, the Reverend Slope.

Lewis was also keen on the enduring value of so-called children’s books, so I have also been re-reading such classics as Tom Sawyer (1876) and Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain, 1884), Treasure Island (R. L. Stevenson, 1883), and (for the first time) Swallows and Amazons (Arthur Ransome, 1930).

All are fascinating, not just because they tell a gripping story (which they do), but because of what they tell about the values of the authors and of the age in which they wrote. Twain, for instance, is writing while racism is still rampant in the US, but at a time when the tide is beginning to turn, in part helped by his novels.

Not that I totally ignore current fiction.

Sometimes I read them simply to discover what all the fuss is about. I have recently read and (sometimes to my surprise) enjoyed The Game of Thrones (George Martin, 1996); The Hunger Games (Suzanne Collins, 2012), which was also a gripping movie; Wolf Hall (Hillary Mantel, 2009); about the time of the English Reformation; and Housekeeping (Marilyn Robinson, 1980), where, as in the author’s other books, her deep Calvinism provides the background colouring.

I also read The Translator (Leila Aboulela, 2006), a story of love across cultures and religions, having heard the author speak at Calvin College’s Festival of Faith and Writing this spring. I was sufficiently impressed that the book is going to appear on my syllabus for the Gospel, Church and Culture course I am teaching this fall, as one of the novels students can choose to read as an illustration of cross-cultural conflict with a faith dimension.

You may be asking: What on earth have these to do with theology or evangelism or mission?

The answer, of course, is “Everything.”

The better we understand the diversity and complexity of our world, and the more we enter into the minds and hearts of people quite unlike us, the better we will be equipped to bring the light of God’s Word to bear on those around us.

This is why, for some years, Calvin College offered a summer school for pastors, where the central activity was simply reading fiction and discussing it together. Such reading, the organisers believed, is one way to apply what the Apostle Paul calls “taking every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Cor 10:5).

The same principle applies to every Christian, whether we are pastors or not.

Summer fiction reading: a great way to combine pleasure and spiritual nurture—wherever you may find yourself. Another cup of tea, anyone?

Do please let us know what you are reading this summer, Just scroll down to the bottom of the page and “Leave a Reply”.

Some highlights from John Bowen’s book, Growing up Christian: Why Young People Stay in Church, Leave Church and (Sometimes) Come Back to Church

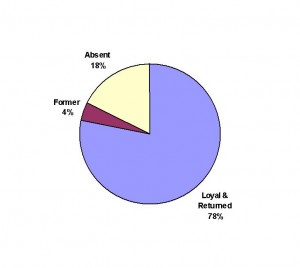

Some highlights from John Bowen’s book, Growing up Christian: Why Young People Stay in Church, Leave Church and (Sometimes) Come Back to Church  “You still call yourself a Christian and are involved in church.” There were 251 who chose this survey, 75% of the respondents. I refer to these as Loyal Believers.Roughly one third of these (eighty-three), although they are active Christians today, had a time of six months or more when they were away from church and/or faith. This is a distinctive group, so I call them Returned Believers.

“You still call yourself a Christian and are involved in church.” There were 251 who chose this survey, 75% of the respondents. I refer to these as Loyal Believers.Roughly one third of these (eighty-three), although they are active Christians today, had a time of six months or more when they were away from church and/or faith. This is a distinctive group, so I call them Returned Believers. Growing up Christian: Why Young People Stay in Church, Leave Church and (Sometimes) Come Back to Church is published by Regent College Publishing (2010), and is available online from Amazon

Growing up Christian: Why Young People Stay in Church, Leave Church and (Sometimes) Come Back to Church is published by Regent College Publishing (2010), and is available online from Amazon