Movies are a place where the spiritual concerns of our culture often intersect with the Gospel. John van Sloten has become well-known in Calgary and around the world for “preaching from the culture.” Here he offers a sermon which analyses a popular current movie in the light of the Christian message.

Movies are a place where the spiritual concerns of our culture often intersect with the Gospel. John van Sloten has become well-known in Calgary and around the world for “preaching from the culture.” Here he offers a sermon which analyses a popular current movie in the light of the Christian message.

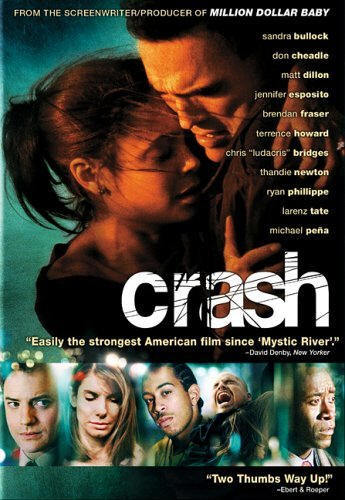

The 2006 Academy Award winning film, Crash, is one of the most profound and powerful films I’ve ever experienced. Its insight into the human condition is piercing; a brutal commentary on our desperate need for God. Unearthing. Disturbing. It wakes you up.

If you’ve ever wondered why we need the Christian story of Easter–its Good Friday darkness and its Sunday morning hope–Crash will give you all the evidence you need. And not very politely–in fact it will sideswipe you. “Nobody leaves this movie unscathed,” says Hollywood director Paul Haggis. He’s right. Culpability is assured: so is grace.

The primary vehicle used in preaching the message of Crash is racism. But not simply racism: it includes all kinds of relational brokenness. A Caucasian gun store owner toward a Persian man; that same Persian man towards an Hispanic locksmith; a corrupt white cop toward a black woman, another black woman toward that same white cop; the rich toward poor, the poor toward the rich; and, last but certainly not least, we, the viewing audience, toward our very selves. In engaging the film, we realize that we’re no different from the story’s characters; we’re just as broken, just as guilty as they are.

The soldiers, having braided a crown from thorns, set it on his head, threw a purple robe over him, and approached him with, “Hail, King of the Jews!” Then they greeted him with slaps in the face. (John 19:2-3, “The Message”)

There’s a scene where two clean-cut young black men are walking along, talking about the unfairness of racism, the discrimination of stereotyping. As a viewer you find yourself walking alongside them, nodding in agreement with their assertions, sharing their incredulity at the injustice of it all. And then, in a shocking twist of plot, the two pull out their concealed weapons and ruthlessly car-jack a rich white couple. All of your broad minded, liberal sensitivities go out the window. Even our stereotypes of relationally broken reality are not as clearly defined as we’d like to think. Good and evil are inextricably intertwined. Crash unpacks us.

A rich white woman screams at her husband regarding her concerns that the tattooed Hispanic locksmith currently working in the next room is a gang member. With him, we’re sickened as we overhear her prejudicial rant; with her, we’re sickened as we overhear ourselves.

And then, in the most disturbing subplot of all, we meet a savior, the only redeemable character in the film; a good white cop named Tommy. We seethe with him at his partner’s blatant bigotry. We stand with him when he’s challenged on his racial idealism. We celebrate human potential with him when he saves a black man, caught in an explosive confrontation with police. And then we die with him when, later in the film, he ends up shooting a young black hitchhiker; all because of a meaningless prejudicial misunderstanding.

Then we cry out in despair with the Apostle Paul:

There’s nobody living right, not even one, nobody who knows the score, nobody alert for God. They’ve all taken the wrong turn; they’ve all wandered down blind alleys. No one’s living right; I can’t find a single one. . . . They never give God the time of day. (Romans 3:10-18, “The Message”)

Everywhere we turn we’re faced with questions. Are we really like this? This perverted? This twisted? Have all of us turned aside and become corrupt? Is there no one who does good, even one? Who’s going to save us from this mess?

The soldiers brought Jesus to Golgotha, meaning “Skull Hill.” They offered him a mild painkiller (wine mixed with myrrh), but he wouldn’t take it. And they nailed him to the cross . . . (Mark 15:22-24, “The Message”)

Putting God on a cross is the ultimate manifestation of human relational brokenness. Depravity is most proudly displayed via our ability to stereotype, prejudice, and reject God. We choose to see what we want to see, we limit the truth; both in the person of Jesus Christ and in ourselves. Somehow we manage to get to the place where we see ourselves as right and God as wrong; it’s the pinnacle of human pride. We become blind to who God really is. One could not conceive of a more tangible way not to “give God the time of day.”

And yet at the very moment that depravity reached its zenith, so too did the providential love of God. While we’re busy hammering in the last few nails, living out our denial based self righteousness, God tearfully looked down on us, at the mess we’d got ourselves into, at the suffering of his Son, and screamed out, “Enough!” And the whole time, Jesus peered straight into our eyes and prayed for us, “Father forgive them.”

The moment we were at our worst, God was at his best. He died, we found life. We sinned, he saved. Our darkness made his light seem even brighter.

And what’s really intriguing about it all is this fact; the whole time this story is playing out, we have no idea what’s going on. We’re being saved behind our backs. While we’re still messed up, and messing up, Jesus died for us.

We can see this same reality playing out in Crash. Throughout the movie, we’re given visual clues every time the camera looks down from above on the city, or on a particular scene, offering us a ‘God’s eye’ view of things. This perspective cues us to the fact that someone is seeing all of this. The storyline goes even further; opening our eyes and hearts to the fact that someone is also mysteriously acting through all of this.

In a powerful scene of redemption, the most despicable character in the film, a bigoted white cop, ends up being the officer on the scene for a terrible car accident. The black woman whose life is hanging in the balance is the same woman he’d physically assaulted the night before. Initially both are horrified at the situation–and then something else mysteriously takes over. A greater good rises up within that peace officer’s heart and he risks his life trying to free her from the burning wreck. She lets go of her anger and trusts him, having no choice but to let him save her. All the while the mystical musical of the movie’s soundtrack plays in the background. Arm in arm they run from the fiery scene, falling into a trembling, tearful embrace. Then the car explodes and the camera pulls up into the sky.

Redemption. Hope. God stepped in and saved them, despite themselves.

God did it for us. Out of sheer generosity he put us in right standing with himself. A pure gift. He got us out of the mess we’re in and restored us to where he always wanted us to be. And he did it by means of Jesus Christ. (Romans 3:24,26-28, “The Message”)

The whole back half of the Crash story is filled with this kind of serendipitous salvation scenes. Saving foisted upon undeserving souls. The whole back half of our life stories are filled with these kinds of serendipitous scenes. It’s what Easter is all about; God at work behind the scenes, resurrecting us in spite of ourselves–mysteriously, graciously, making all things new.

At the time this was written, John van Sloten was the founding pastor of New Hope Community Church (CRC) in Calgary AB.