Evangelism has been a preoccupation in many mainline denominations over the past twenty years or so. On one level, this may simply have been a panic reaction to declining numbers and the feeling that evangelism is one way to “get people back to church. My own church, the Anglican Church, was not untypical in proclaiming the 1990s a Decade of Evangelism.

Evangelism has been a preoccupation in many mainline denominations over the past twenty years or so. On one level, this may simply have been a panic reaction to declining numbers and the feeling that evangelism is one way to “get people back to church. My own church, the Anglican Church, was not untypical in proclaiming the 1990s a Decade of Evangelism.

On a more substantial level, the renewed interest is a reflection of the gradual reinstatement of evangelism as a legitimate aspect of the mission dei over the past fifty years. David Bosch in his magisterial Transforming Mission has traced the development of this new understanding of mission, attributing it to changes both on the ecumenical side and on the evangelical side:

[A]n important segment of evangelicalism appears poised to . . . embody anew a full-orbed gospel of the irrupting reign of God not only in individual lives but also in society. A similar turning of the tide, but in the opposite direction, has been in evidence in ecumenical circles since the middle of the 1970s.On the one side, evangelicals have softened their suspicion of the “social Gospel”, so that an evangelical leader such as John Stott, interacting with ecumenical concerns about evangelism, could write as long ago as 1975 that:

“Mission” describes . . . everything that the church is sent into the world to do. “Mission” embraces the church’s double vocation of service to be “the salt of the earth’”[social concern] and “the light of the world” [evangelism].

This has served to reduce the caricature of evangelism which frequently exists in mainline churches that evangelism is necessarily an insensitive, hypocritical verbal exercise.

On the other side, a writer like Lesslie Newbigin, not an evangelical, but in a book published (significantly enough) jointly by Eerdmans and the World Council of Churches, has also written of the place of evangelism in the broad scope of the missio dei:

[T]he [New Testament] preaching is an explanation of the healings. . . . [T]he healings . . . do not explain themselves. They could be misinterpreted . . . The works by themselves did not convey the new fact. That has to be stated in plain words: “The kingdom of God has drawn near.

Thus there has been a remarkable move away from the polarization of a previous generation and a convergence of opinion that the missio dei embraces both word and action (Bosch says simply, “Words interpret deeds and deeds validate words” ) and that both are the responsibility of the church.

These two impulses “the one to seek new church members, and the other a theological convergence” have led in recent years to a flood of books on the subject of evangelism, with authors as surprising as Walter Brueggemann , and titles as startling as The Celtic Way of Evangelism. Many seek to define evangelism, and, while there are variations, most are summed up by John Stott’s simple definition: “Evangelism is to preach the Gospel.”

Of course, the idea of “preaching the Gospel” is hardly new. The use of the term “evangelism” itself may be a relatively recent innovation (the first recorded use of the term is in the writings of Francis Bacon in the 16th century), and the methodology of evangelism has since the nineteenth century often been modernist, but the impulse to evangelism is as old as Christianity itself.

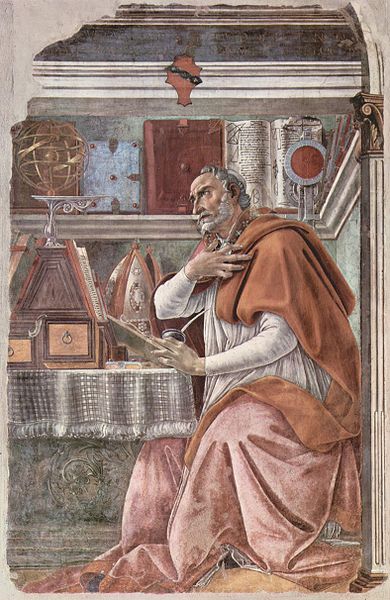

This article will consider how Augustine in the Confessions describes his own experience of evangelism–or, rather, of being evangelized–and will then compare Augustine’s understanding of this experience with contemporary definitions of evangelism, and consider what the church today (not least the mainline church) can learn from this ancient example. I will consider the topic from three points-of-view: Augustine’s own (his theological interpretation of what happened to him), what I can only call a theocentric view (as Augustine understands God’s part in his conversion), and the church’s view (since the church is the locus of the work of evangelism, as of other aspects of the missio dei).

(a) Augustine’s point-of-view

Augustine’s story illustrates what has almost become a cliché in contemporary discourse about evangelism–that evangelism is a process – in the case of Augustine, a process that took over eleven years. Several factors were involved in the process, beginning with his turning away from childhood faith.

Augustine’s departure from Christian faith was similar to that of many people from a church background: a combination of growing up and experimenting with new things in life on the one hand, and, on the other hand, not finding adequate intellectual and spiritual nurture in his “faith of origin.” Thus, at the age of seventeen, he left home and went to Carthage. There, he says:

I had not yet fallen in love, but I was in love with the idea of it . . . I had no liking for the safe path without pitfalls. (3:1, 55)

In Carthage, he left “the safe path” and discovered the “pitfalls” of love and the theatre. To a casual observer, this might just look like a young man sowing his wild oats. With the benefit of hindsight, however, Augustine reads this period differently, arguing that what he was doing was far more serious than that: he was in fact doing what all sinful human beings tend to do: putting the creature in place of the Creator:

[M]y sin was this, that I looked for pleasure, beauty and truth not in [God] but in myself and his other creatures, and the search led me instead to pain, confusion, and error. (1:20, 40)Because the essence of his leaving the faith was the desire to be his own God, the heart of the return will be a reversal of this, in other words, allowing God God’s rightful place in his life.

However far Augustine drifted from his childhood faith, a spiritual hunger was never far below the surface. When he said, “Our hearts are restless till they find their rest in you” (1:1, 21), he spoke from personal experience. His first attempt to assuage that hunger was with the Manichees, which whom he experienced what Peter Brown calls “his first religious conversion.” Before long, however, he found he had doubts about the Manichees’ claims, and his spiritual hunger remained unsatisfied:

I gulped down this [the Manichees’] food because I thought that it was you. . . . And it did not nourish me, but starved me all the more. (3:6, 61)

He describes two blows in particular to his faith in Manicheism. Firstly, Firminus advised him to reject Manichean astrology as irrational:

In a kind and fatherly way he advised me to throw [the books of astrology] away and waste no further pains upon such rubbish, because there were other more valuable things to be done. (4:3, 74)

Then, secondly, at the age of 29, he met Faustus, reputed to be a great authority on Manicheism, whom he had hoped would answer all his questions, but Augustine was disappointed with Faustus’ superficiality, and said: “I began to lose hope that he could lift the veil and resolve the problems which perplexed me” (5:10, 104). In terms of the parable of the sower (perhaps the source of all understanding of evangelism as process), Augustine’s disillusionment with Manicheism broke up the ground in which the seed of the Gospel could be sown, or rather revived.

The next step in the process was that Augustine needed to hear the Gospel in a different form from that in which he had heard it in his youth. Under the influence of Ambrose’s preaching, Augustine “discovered how different Christian faith is from what he had supposed.” (Chadwick xx) (It is interesting that even today new converts, for example, through the Alpha program, will often speak of having discovered a Christianity that is quite different from what they had thought.) Some of this was the unlearning of his misconceptions about orthodox Christianity. For example:

I learned that your spiritual children . . . do not understand the words “God made man in his own image” to mean that you are limited by the shape of a human body. (6:3, 114)

Augustine describes this stage of learning what the church does not in fact teach thus:

Though I had not yet discovered that what the church taught was the truth, at least I had learned that she did not teach the doctrines which I so strongly denounced. (6:4, 115)

He also heard better explanation of scripture than he had encountered in Africa:

As for the passages which had previously struck me as absurd, now that I had heard reasonable explanations of many of them, I regarded them as of the nature of profound mysteries. (6:5, 117)

Thus the good seed of “the word” was sown into ground that had been well-prepared.

The turning point itself took place through the reading of a verse of scripture which he interpreted as exactly suited to his circumstances:

“Not in reveling and drunkenness, not in lust and wantonness, not in quarrels and rivalries. Rather, arm yourself with the Lord Jesus Christ; spend no more thought on nature or nature’s appetites.” (Romans 13:13-14) (8:12, 178)

The verse describes two ways of living, one in self-indulgence, the other in relationship to Christ: he chose the latter. The movement from this point towards baptism is apparently straightforward and lacking in the kind of emotional angst that has accompanied his journey so far, and described with far more economy. Later, he will describe this series of events in terms of giving up his freedom and yielding control of his life to his Creator:

You know how great a change you have worked in me, for first of all you have cured me of the desire to assert my claim of liberty . . . [Y]ou have curbed my pride by teaching me to fear you and have tamed my neck to your yoke. (10:36, 244)

For Augustine, if the essence of sin is putting ourselves in the place of God, then the heart of conversion is acknowledging the rightful place of God in our lives. This is the substance of what happens to Augustine as the process of evangelism leads to his conversion.

Although Jesus’ parables of sowing and reaping suggest the idea of process in the life of faith, Augustine, perhaps surprisingly, does not use agricultural imagery, but prefers a different image for process, that of the journey. At various points in the Confessions, he interprets his life as “the road to conversion” (6:4, 115):

So, step by step, my thoughts moved on from the consideration of material things to the soul. (7:17, 151)

From time to time, the parable of the prodigal son is clearly in the background of this image. Twice Augustine casts himself in the role of prodigal:

The path that leads us away from you and brings us back again is not measured by footsteps or milestones. . . . [The prodigal’s] blindness was the measure of the distance he travelled away from you, so that he could not see your face. (1:18, 38)

Where were you in those days? How far away from me? I was wandering far from you and I was not even allowed to eat the husks on which I fed the swine. (3:6, 62)

He further understands that the Christian life itself (when he finally adopts it) will be a road on which the believer follows Jesus. For instance, when he goes to ask advice of Simplicianus, he wants to enquire “how best a man in my state of mind might walk upon your way.” (8:1, 157) Picking up Jesus’ own language of “the narrow way,” he adds:

[I]n my worldly life all was confusion. . . . I should have been glad to follow the right road, to follow our Saviour himself, but I could not make up my mind to venture along the narrow path. (8:1, 157)So much for Augustine’s own mature reading of how the road led him by a circuitous route to Christian faith. The story looks somewhat different, however, when viewed from what Augustine understands to be:

2. A theocentric point-of-view

Augustine is deeply convinced that the work of drawing people into the Kingdom of God is the work of God. Evangelism is something only God can do. It is God who wants reconciliation with sinners, God who pursues them, God who draws them into relationship. Augustine’s convictions about the sovereignty of God mean that he understands God’s grace to precede any human activity: “My God, you had mercy on me before I had confessed to you” (3:7, 62) and knows from experience that “Man’s heart may be hard, but it cannot resist the touch of your hand.” (5:1, 91)

So how, from Augustine’s point-of-view, does God bring evangelism about? How does God bring people into the Kingdom? Augustine offers several clues in the Confessions.

One is that a sovereign God works through circumstances. As Augustine looks back, he sees God at work, even when he (Augustine) was not aware of it, to create situations that would move him towards faith. Thus, for instance, when Augustine moved from Carthage to Rome because he had heard that the students were quieter:

It was . . . by your guidance that I was persuaded to go to Rome. . . . [I]t was to save my soul that you obliged me to go and live elsewhere. . . . You applied the spur that would drive me away from Carthage and offered me enticements that would draw me to Rome . . . In secret you were using my own perversity . . . to set my feet upon the right course. (5:8, 100)

Augustine uses the metaphor of a ship helpless before the wind being steered by the helmsman to illustrate this sense of being moved irresistibly towards faith:

In my pride I was running adrift, at the mercy of every wind. You were guiding me as a helmsman steers a ship, but the course you steered was beyond my understanding. (4:14, 84)

Chadwick comments:

Decisions made with no element of Christian motive, without any questing for God or truth, brought him to where his Maker wanted him to be.

One aspect of this providential overseeing of circumstances is expressed in Augustine’s conviction that God allows difficulties in order to draw people like himself to faith. Thus Augustine found that his road of independence from God was not an easy road. At every turn, he found difficulty. On one level, Augustine sees this as simply the “natural” effect of moving away from God. He says: “[E]very soul that sins brings its own punishment upon itself.” (1:12, 33)

Yet he also attributes these difficulties to the direct hand of God, as a spur or goad to drive him back onto the right road. Even in his relationship to his concubine, which appears to have been a loving and generally satisfactory relationship, he observes that God “mixed much bitterness in that cup of pleasure.” (3:1, 55) We know that his mother prayed for him, and “Her prayers reached your presence, and yet you still left me to twist and turn in the dark.” (3:11, 68) Maybe the answer to her prayers was that he should twist and turn in the dark he had chosen—at least for a time. God’s love, in Augustine’s experience, is not soft!

It almost seems as though, the nearer he approaches to the truth, the more intense his suffering becomes. Although by the time he reaches Milan he begins to “prefer the Catholic teaching” (6:5, 116) and discovers the neo-Platonists, he is still miserable, finding he has less joy in life than a poor beggar. He attributes this too to the hand of God, seeking to turn him in the right direction, and, as so often, turns to the Psalms for a template through which to interpret his experience:

My soul was in a state of misery and you probed its wound to the quick, pricking it on to leave all else and turn to you to be healed. . . . [Y]ou broke my bones with the rod of your discipline. (6:6, 118)

Augustine observes also that he was moved towards faith through those who themselves do not have faith, and interprets this as a further sign of God’s sovereign power. Thus the influence that set him on the road that would eventually bring him back to Christian faith was his discovery at the age of 19 of Cicero, who “altered my outlook on life. It changed my prayers to you, O Lord, and provided me with new hopes and aspirations” (3:4, 58). It was Cicero [106-43 BC], not any Christian or biblical writer, who first caused Augustine to take his soul seriously, and to seek wisdom as a means to nurturing that soul.

The second example comes from much later, when he was relearning Christian faith, and he discovered Plotinus, the neo-Platonist, and was amazed to find much that was compatible and indeed fulfilled in Christianity. As Simplicianus explained to him, “In the Platonists . . . God and his Word are constantly implied.” (8:2, 159) The difference is that while Platonism sees the goal, it does not see how to get there:

It is one thing to descry the land of peace from a wooded hilltop and, unable to find the way to it, struggle on through trackless waters . . . It is another thing to follow the high road to that land of peace, the way that is defended by the heavenly Commander. (7:21, 156)

Plotinus, however, like Cicero before him, points Augustine in the right direction, and thus serves as a proto-evangelium. Augustine is at this point somewhat like C.S.Lewis, who, having been convinced by J.R.R.Tolkien that pagan myth merely foreshadowed Christian truth, described himself as “a man of snow at long last beginning to melt.”

As Augustine later realized, this was why the Apostle Paul’s evangelistic strategy with the pagans of Athens had not been to argue from the Old Testament, but to begin with their own poets (Acts 17):

Through your apostle you told the Athenians that it is in you that we live and move and have our being . . . And, of course, the books that I was reading were written in Athens.” (7:9, 146)

God, then, works through unbelievers, sometimes those who are seeking truth (like Cicero, Plotinus, and the Athenian poets of Acts 17), sometimes those who are indifferent or even (like those who encouraged Augustine to go to Rome) “whose hearts were set upon this life of death.” (5:8, 100)

Yet Augustine knows that his movement towards faith is not merely the existential wrestling of one man with his God, and his description makes clear that others are involved in the process. Thus he sheds light on what we might call:

3. The Church’s point-of-view

C.S.Lewis somewhere suggests, perhaps whimsically, that God does not do anything alone that God is able to delegate to human beings , and as the Confessions unfold, it is clear that Augustine encountered many people who helped him along his path. While he acknowledges that a sovereign God speaks and works through unbelievers who do not realize their instrumentality, he finds that God also speaks and works through believers in the Christian community. Monica provides the earliest instance of this. Thus, when he reached adolescence and relative independence, she:

earnestly warned me not to commit fornication and above all not to seduce any man’s wife. . . . the words were yours, though I did not know it. I thought that you were silent and that she was speaking, but all the while you were speaking to me through her, and, when I disregarded her, . . . I was disregarding you (2:3, 46)

Not surprisingly, when Augustine later moved from Carthage to Rome, he tricked Monica into not coming with her. Yet the Hound of Heaven was able to find other mouthpieces. For example, when Firminus sowed seeds of disillusionment with Manicheism, Augustine recognized later that once again God was speaking to him:

This answer [of Firminus] which he gave me, or rather, which I heard from his lips, must surely have come from you, my God. (4:3, 74)

God also speaks through the testimony of converts. Particularly as Augustine’s story moves towards its climax, there is a flurry of people whose experience finally catalyzes his conversion. First, when he goes to consult Simplicianus, “spiritual father of Ambrose”, Simplicianus tells him the story of the conversion of Victorinus, also “a professor of rhetoric, an admirer of the pagan Platonists, at best, merely tolerant of Catholicism.” (Brown 103) Augustine is no fool, and he knows exactly what is happening:

I began to glow with fervour to imitate him. This, of course, was why Simplicianus had told [the story] to me. (8:5, 164)

Shortly afterwards, Ponticianus tells Augustine and Alypius the story of Antony; then of two other converts who became Christians through reading the story of Antony. (8:6) Through these stories, his heavenly pursuer closes in:

[W]hile he was speaking, O Lord, you were turning me around to look at myself. . . . I saw it all and was aghast, but there was no place where I could escape from myself. (8:7, 169)It is not only the words Christians speak, however, which move Augustine in the direction of faith. Witness is normally by life as well as by words: indeed, the life gives credibility to the words and the words interpret the life. Thus Augustine first experiences the love of God through God’s servants. Monica, of course, is the outstanding example for Augustine of one who lives out the teaching of Christ, and what he says of her influence on her husband Patricius he could equally have said of her influence on him:

[T]he virtues with which you had adorned her, and for which he respected, loved and admired her, were like so many voices constantly speaking to him of you. (9:9, 194)But Monica is the not the only one whose quality of life struck Augustine. On arriving in Milan, he met Ambrose, who:

received me like a father and, as bishop, told me how glad he was that I had come. My heart warmed to him, not at first as a teacher of the truth . . . but simply as a man who showed me kindness. (5:13, 107)

As Chadwick comments, Ambrose was “was everything a bishop ought to be.” (Chadwick xxv) As for so many people, it was not only the ideas of Christianity which attracted Augustine, but also those truths incarnated in the flesh of real human beings.

Augustine comes to believe too that God works through the prayers of the church. Monica is a woman who prays, and in particular, she prays for her son. When he moved away from the practice of his faith, he says:

[M]y mother . . . wept to you for me, shedding more tears for my spiritual death than other mothers shed for the bodily death of a son. (3:11, 68)This too can be understood as human partnership with God. As Pascal put it, God gives us prayer so that we may have the dignity of causality. Certainly prayer was one of the ways in which Augustine believed Monica influenced him. He was impressed by the elderly bishop who assured her, “It cannot be that the son of these tears should be lost.” (3:12, 69)

Conclusion

Augustine’s experience of coming to faith suggests that while Stott’s definition of evangelism as “preaching the Gospel” is not untrue (Augustine did hear Ambrose preach the Gospel, after all), it is unhelpful in that it masks the complexity of the process.

Another author, who offers a broader definition which comes closer to encompassing the many facets of Augustine’s experience, is William Abraham. He suggests that evangelism is:

that set of intentional activities which is governed by the goal of initiating people into the kingdom of God for the first time. . . . [Thus] evangelism is . . . more like farming or educating than like raising one’s arm or blowing a kiss.

The evangelizing of Augustine is certainly not a single activity: it is spread over many years, and involves a wide variety of friendships, difficulties, conversations, prayers, encounters, readings, disagreements, self-examinations, mentors, false starts, scripture, and (in the end) a dramatic conversion. “Farming” and “education” might indeed be suitable metaphors for this process.

Even now, however, there are problems with the definition. Would it be right, for example, to call what happened to Augustine “a set of intentional activities”? Certainly Monica is clear about her intentions for her son; certainly Simplicianus is intentional in pointing Augustine towards Christ (even Augustine could see that); and Ambrose was undoubtedly aware in his sermon preparation of who was going to be listening. They all have, as it were, evangelistic intentions. But if there is an overarching intention, linking all these influences, it can only be (to speak Augustine’s language) in the mind of God, who oversees this process from beginning to end. Certainly the resources of the church are brought to bear on him—prayer, counsel, witness, and preaching, for example—but the human evangelists can claim no more than that they are co-workers together with God in God’s work of evangelism.

In light of Augustine’s experience and his reflection on that experience, then, we might expand Abraham’s definition to suggest that:

Evangelism is the work of God through people, specially the church, and circumstances, whose goal is the initiation of people into the Kingdom of God. Evangelism is like farming or educating, a process taking place over time and through countless and varied influences, whose effect is cumulative, and all of which point to faith in Christ. Evangelism is therefore the work of the church as it co-operates with God the supreme evangelist.

Augustine’s Confessions thus provides a salutary corrective for a contemporary theology and praxis of evangelism. In particular, the Confessions point us away from any sense that evangelism is a matter between the individual and God alone, that the key is in an existential and instantaneous “decision”, or that the church’s activism will bring it about. In fact, what the Confessions offers is a pre-modern corrective to a modernistic distortion of evangelism—an understanding that will, ironically enough, equip the church for evangelism in a postmodern world.

The Toronto Journal of Theology, Spring 2007

Notes:

- To paraphrase Don Posterski, evangelism has been brought out of the red light district of the church and onto the main street of church life. John P. Bowen, Evangelism for ‘Normal’ People (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress 2002), 16.

- David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll: Orbis 1991), 408. His Chapter 12, “Elements of an Emerging Ecumenical Missionary Paradigm”, from which this is taken, is illuminating both historically and theologically.

- John R.W.Stott, Christian Mission in the Modern World (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1975), 30.

- Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans and WCC 1989), 132.

- Bosch 420.

- Walter Brueggemann, Biblical Perspectives on Evangelism: Living in a Three-Storied Universe (Nashville: Abingdon, 1993).

- George G. III Hunter, The Celtic Way of Evangelism: How Christianity can reach the West . . . Again (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000).

- Stott 39.

- A superficial survey reveals that this is a theme for a wide range of writers including William J. Abraham, The Logic of Evangelism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1989), Becky Manley Pippert Out of the Saltshaker (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2nd edition, 1999), George G. Hunter, The Celtic Way of Evangelism (Nashville: Abingdon 1999), Richard V. Peace Conversion in the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1999) and John P. Bowen, Evangelism for ‘Normal’ People (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress 2002).

- David Lodge, using the language of semiotician A.J.Greimas, would have us describe Augustine’s process of moving away from Christian faith and then returning to it, as a “disjunctive journey,” which he defines as “a story of departure and return . . . In this kind of story, the hero and his companions venture out, away from secure home ground, into foreign and hostile territory . . . then return home, exalted or chastened by the experience.” David Lodge Write On (London: Secker and Warburg, 1986), 157.

- Actually, as Peter Brown points out, in spite of his description of Carthage as a “hissing cauldron of lust” (3:1, 55), within a year he had settled down with a mistress to whom he was faithful for fifteen years. Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1968), 39.

- Brown, 39.

- This imagery of “steps” does not sit well with Karl Barth, who demands: “Is the function of the revelation of God merely that of leading us from one step to the next within the all-embracing reality of divine revelation?” Emil Brunner, Natural Theology: Comprising “Nature and Grace” by Professor Emil Brunner and the reply “No!” by Dr. Karl Barth (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1946), 82.

- He uses the image of the spur or goad twice more: “[Y]our goad was thrusting at my heart, giving me no peace . . .” (7:8, 144); “[Y]ou tamed me by pricking my heart with your goad.” (9:4, 185) In all three instances, his word stimulus is the same as that used in the Vulgate of Acts 26:14, Paul’s account of his conversion: “it hurts . . . to kick against the goads.”

- Cf. “You were my helmsman when I ran adrift” (6:6, 118)

- Augustine, Confessions, ed. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1998), xxi.

- This is consistent with the theology of such biblical writers as Isaiah, who has Yahweh refer to the pagan King Cyrus as “my servant” (Isaiah 45:1), and makes use of him to accomplish God’s purposes.

- C.S.Lewis, Surprised by Joy (London: Fontana Books 1959), 179. He explains elsewhere that what Tolkien showed him was that “the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds of the poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call ‘real things’.” Walter Hooper, ed. The Letters of C.S.Lewis to Arthur Greaves (New York: Collier Books 1979), 427.

- “Creation seems to be delegation through and through. He will do nothing simply of Himself which can be done by creatures.” C.S.Lewis, Prayer: Letters to Malcolm (London: Geoffrey Bles 1964; London: Fontana Books 1988), 73.

- Jesus seems actually to have foreseen this kind of connection: “Whoever listens to you listens to me, and whoever rejects you rejects me.” (Luke 10:16)

- cf. Bowen, chapter 4.

- cf. “[A]ll the time this chaste, devout and prudent woman . . . never ceased to pray at all hours and to offer you the tears she shed for me. . . . Her prayers reached your presence.” (3:11, 68)

- “Why God has established prayer. 1. To communicate to His creatures the dignity of causality.” Blaise Pascal, Pensees in The Harvard Classics, volume XLVIII, ed. Charles W. Eliot (New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–1917).

- William Abraham, The Logic of Evangelism ( Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1989), 95, 104.