The image of God we carry around in our head is one of the most important things about us. Accurate and inaccurate images of God can lead to very different conclusions. For instance, many people have the image of God as very religious. But, from the teaching of Jesus at least, that is a pretty inadequate image. For one thing, the God Jesus believed in is the creator of all of life—not just the religious dimension of it.

The image of God we carry around in our head is one of the most important things about us. Accurate and inaccurate images of God can lead to very different conclusions. For instance, many people have the image of God as very religious. But, from the teaching of Jesus at least, that is a pretty inadequate image. For one thing, the God Jesus believed in is the creator of all of life—not just the religious dimension of it.

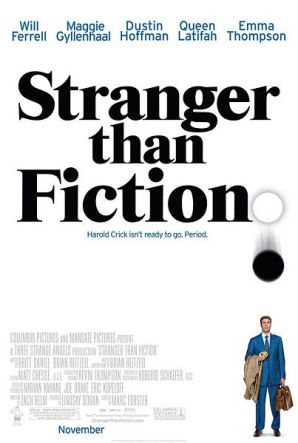

One implication of this is that, if God wants to communicate with us, God does not have to wait till we take an interest in religion. God can begin to communicate with us through all sorts of things—through friends, through our school work, through circumstances—or even through a movie which raises spiritual questions. For me, Stranger than Fiction is just one of those movies.

Let me tell you what I want to do. I want to offer what English students will recognize as a kind of whimsical “reader response” to Stranger than Fiction. I’m not claiming that this is what the director or the script-writer “meant”: I’m simply saying, these are some of the resonances the movie had for me as a Christian.

One reason I want to do this is that I find that many people have never heard an explanation of Christianity that they could understand. They’ve heard some that were horribly religious, or made outrageous assumptions, or used weird technical language, or just seemed too ludicrous to believe.

I’m hoping that explaining Christian faith with the help of the movie will help it make sense to you. If you are not a follower of Jesus, I don’t expect that it will make you a follower of Jesus by the end. But if you get to the point of saying, OK, I think I have a clearer sense of what Christianity is all about, I will be very happy, because then you can make an informed decision about it. And of course that clearer understanding may also be something that God is wanting to communicate to you right now!

First of all let me remind you of:

The story

[Beware: spoilers ahead!]

The story revolves around Harold Crick, played by Will Ferrell. Harold is an IRS audit agent and (among other things) a numbers nerd—he counts the number of times he brushes each tooth, the number of steps to his bus stop, and so on. We are introduced to Harold by a voice (a woman’s voice, English, upper class, and with that hint of sarcasm which is so typically English), which describes what’s happening.

But then Harold begins to hear the voice too. First of all he’s alarmed, then irritated by the voice. Who the heck is this? How does she know so much about his life? And, of course, the $1,000 question: What is the connection between what he does and what she says? Is she just describing what he chooses to do? or is he simply carrying out what she describes? Whose life is this anyway?

Then he notices that his watch has stopped. He resets it, and the voice says, “Little did he know that this seemingly innocent act would result in his imminent death.” Now Harold is really scared. He goes to a psychiatrist (Linda Hunt) who decides that it’s simply a case of schizophrenia. But his problem is about a story, so he goes to see an expert in stories—Jules Hilbert, an English prof (played by Dustin Hoffman).

One thing Hilbert suggests is that Harold should find out whether his story is a comedy or a tragedy. That way he will know whether it has a happy ending or not. By this time he is falling in love with the owner of a bakery whom he’s auditing, Ana Pascal (played by Maggie Gyllenhall), so he tries to keep a note of whether the progress of their relationship indicates tragedy or comedy. For a time tragedy seems to be way ahead.

But then it seems that, against the odds, Ana is falling for Harold, and Hilbert says this means it’s a comedy: this wouldn’t happen in a tragedy.

Then Harold hears the voice of his narrator on TV, and Hilbert recognizes her. It’s Karen Eiffel, a reclusive novelist. He says, “She only writes tragedies. She kills people.” In particular, she always kills off her main characters.

Harold discovers her phone number among the IRS records, and phones her. Then, in one of the most dramatic moments in the movie, just as she is typing, “The phone rang,” the phone rings. She is startled. Is it a coincidence? She types, “The phone rang again,” waits a second, and sure enough the phone rings again. With rising panic, she types, “The phone rang a third time”—and of course it does. And so the author and her main character come face to face.

He asks Karen if he’s already dead. The fact is that she has the ending in draft form, but it’s not yet typed. Her assistant Penny suggests she should let Harold read the manuscript. He tries, but (not surprisingly) finds he can’t do it, so he asks Hilbert to do it for him. Hilbert’s conclusion is not encouraging: “Harold, I’m sorry. You have to die. . . . It’s her masterpiece. . . . It’s absolutely no good unless you die in the end.” Harold replies (as I suppose any of us would): “I can’t die right now. This is really bad timing.”

But then Harold reads the book for himself, and here comes a turning point in the story: he changes his mind. He tells Karen: “I love your book and I think you should finish it.” And so he commits himself to acting out the end of the script . . . And that’s as much as I’m going to tell you.

To me, this movie illustrates a number of significant themes in Christian spirituality.

1. Sin

One of the biggest themes in the story is the tension between the author and the character. The Emma Thompson character is a kind of God-figure, with power of life and death. In the movie, as far as we can tell, Harold can’t change the course of the story: this seems to be confirmed when the wreckers begin to dismantle his apartment. He can ask the author to change it, but she has the last word.

In Christian spirituality, one way to think of God is as the Author of the human story. (It’s a bit more accessible than God as the King or God as the Lord, since we don’t have kings and lords in our world, but we do have authors!)

Our job as human beings is to play our part in the story. It’s not quite the same as Harold in relation to Karen Eiffel, because the way Christians understand this idea of God’s story is that we have been given freedom—not the illusion of freedom (as Harold has the illusion of freedom), but true freedom. So there’s a tension that comes from thinking of God like this: on the one hand, God is writing a story but on the other hand, we have the freedom to play our part, but also the freedom to say no. How can we follow a script and be free at the same time?

I would say the place to look is at Jesus. Because on the one hand, he can say, “I always do those things that please my father” (his favourite way of talking about God): so he’s obviously committed to living out God’s script. But nobody ever accused Jesus of being a mindless robot. When you read his biographies, he lives with passion and creativity and individuality. He’s somehow more alive than anyone around him. When he’s arguing with his enemies, he’s very light on his feet, and almost impossible to catch out. So it’s a funny paradox: it looks as though freely living in God’s story actually makes you more yourself, not less. (We’ll come back to that at the end.)

But, like Harold, we have some disagreements with the author. We may not like the way the story is going. Sometimes we don’t care for the part that’s been written for us. Sometimes the story requires us to be unselfish, or forgiving, or generous, and we don’t feel like it.

I don’t know how you would define sin if you had to. . . . One definition I find helpful it to think that sin is insisting on writing my own script.

2. Incarnation

In some ways, Harold is like Jesus, figuring out how to live in the story. But in other ways, Jesus is more like another character. Let me come at it this way: you may have heard Christians say things like: “Jesus came down from heaven”—which sounds remarkably like Superman coming to earth from the planet Krypton, which is a childish kind of image. C.S.Lewis suggested what I think is a more helpful and accurate image. He said:

Shakespeare could, in principle, make himself appear as Author within the play, and write a dialogue between Hamlet and himself. The “Shakespeare” within the play would of course be at once Shakespeare and one of Shakespeare’s creatures.

Jesus didn’t travel through space or time to be present in our world. He “moved” (and even that is a metaphor) from one mode of being to another. So the person we meet in Jesus is the Author who has written himself into the script of our story.

What’s clever about Stranger than Fiction, of course, is that the author lives in the same world as her creation. Normally authors and their characters live in different worlds, which is why Lewis’ analogy can work. But by putting Karen Eiffel in the same world as Harold, the movie actually gives us a glimpse of what Jesus is like—not a neurotic chain smoker who imagines committing suicide, of course, but a human being who is approachable and who understands our problems. Because, of course, when Karen learns that Harold is a real person, she understands instinctively how difficult it must be for him to be part of her story. And when Harold learns that his author is in the same world as him, he can find her phone number and go and talk to her.

So when Christians talk about prayer, they’re not thinking about talking to a distant, vague kind of God. They believe they’re talking to a God who has been a part of our world, who knows from personal experience what it’s like to be a human being, who has experienced hunger and suffering, joy and sadness, who has hung out with friends and who’s been let down by friends—and (ultimately) a God who has experienced death.

That’s the Christian doctrine called Incarnation.

3. Atonement

Talking of death, there’s another point at which Harold is both similar to Jesus and deeply different from Jesus: they both know they’re going to die, but they respond differently to knowing that.

In Harold’s case, one of the turning points in the movie is when the voice announces calmly, “Little did he know that this seemingly innocent act would result in his imminent death.” So . . . what do you do if you know you’re going to die? Jules Hilbert has an answer. He advises Harold that, if he knows he’s going to die, he should just live the life he’s always wanted, do whatever he wants to do: which he does. He stops wearing a tie, starts wearing a red sweater (very daring, for Harold); he stops counting tooth brush strokes; he learns to play the guitar, something he’s always wanted to do; he goes to funny movies; and he makes love to Ana. In the end, of course, Harold does something unselfish, but that’s not his first response to accepting that he’s going to die. It’s simply to have a good time.

For Jesus, the knowledge that he’s going to die doesn’t come via a voice from the sky. The realization seems to grow slowly on him: he experiences increasing opposition from powerful forces in his world, and sees intuitively how this is going to end. So about halfway through his biographies, he begins to warn his followers that this is going to happen. His response to knowing he’s going to die is different from Harold’s. Instead of just doing whatever he has always wanted to do, he continues to give his life for others every day—the sick, the lonely, the bereaved, the marginalized: so that what happens on the cross on the first Good Friday is just the logical climax of what he’s done every day.

Christians call this the Atonement: Christ’s ultimate giving of himself for humankind’s ultimate problem.

4. Revelation & Eschatology

Another theme of the movie is the question of tragedy and comedy. Will Harold’s story have a happy ending or a sad ending? You can ask the same question about this image of the Christian story. Is it a tragedy or a comedy? Certainly, when you look at some people’s lives, they seem like an unending tragedy.

But I learn two things from Harold: one is that, left to our own devices, it’s very difficult to decide which is true. First of all, he thinks his story must be a tragedy (Ana doesn’t love him), then he decides it’s a comedy (Ana does love him), then it goes back to being a tragedy (Eiffel only writes tragedies), and finally . . . Well, even if you haven’t seen the movie, the fact that it is a Hollywood movie means you can guess what kind of ending it will be.

But the second thing I learn from Harold is that your life does make sense once you read the whole story. When Harold reads the whole script, he realises that it all makes sense. He says, “I read it and I loved it and there’s only one way it can end.” He stops trying to escape his death: he sees how it fits into the story, and he agrees to act it out. It’s a tragedy, sure, but it’s a great tragedy.

Christians believe that the Bible is God showing us at least the outline of the story he is writing. The story is about a good and beautiful world that has gone horribly wrong, and of a Creator who intervenes in the world to put things right. And (guess what?) when you get to the end of the story, in spite of all the awful things that happen between the beginning and the end, it’s actually a comedy—the divine comedy.

I remember once explaining the difference to my kids: that the arc of tragedy is upward—Macbeth succumbs to pride, and rises slowly and violently to power, but then he is brought down and things revert to normal. The arc of comedy, however, is the other way up. Things start OK, but then they begin to go wrong, and get more and more confused until you think they will never get resolved—but then in the end, everything is straightened out and everyone lives happily ever after. And my daughter Anna said, “You mean it’s like a happy face and a frowny face?” Which I guess it is.

God’s story, as Christians understand it, is ultimately a comedy. For anyone who chooses to co-operate with the Author, whatever happens along the way, the ending is always a happy one. And this is true even though death is always a part of the equation—Jesus demonstrated that. Death never has the last word: the last word in God’s story always goes to joy.

This idea that God has given us a glimpse of the whole story is what theologians call “revelation.” And the study of how the story is going to end is what they like to call “eschatology.”

5. Gospel

The last thing I have been thinking about is an idea that’s not in the movie, but it is in the Christian story, and it’s this: that the Author is trying to get our attention. In the movie, it’s the other way round: the character is trying to get the attention of the Author, who doesn’t know he exists. In God’s story, the way Christians understand it, the Author is trying to get the character’s attention, even though the character may not believe in the Author! God tries to get our attention through any number of means: through friends—Christians who don’t fit the caricature the media feed us; or it may be ideas about meaning and reality that keep coming back to us and nagging at us; or an answer to prayer that we prayed when we were desperate and we think in alarm, Maybe there is a God who’s interested in me. There are a thousand ways God can try to get our attention. Even, of course, movies that make us think about spiritual questions.

And why might God want to get our attention? In the movie, the reason Harold wants to track down Karen Eiffel is to get her attention before she kills him.

In the Christian story, the Creator’s story of the world, the Author wants us to pay attention because God loves us. God designed human beings so they work best in relationship to him. But if we keep trying to run our own lives, write our own pathetic little stories, naturally we will run into trouble. There is no story you could write for yourself, or a story your culture could write for you, which will be as good as the story the God who created you is writing for you.

Here is the last technical Christian term I’ll offer you: Gospel. Gospel means good news, and Gospel has always been at the heart of Christianity. So what is this Gospel, this good news? Here’s one way to say it: the good news is that by following Jesus, you can become the person God created you to be, and you can play your part in the great story, the Divine Comedy, God is writing about this world.

Like Harold, we can say Yes to the Author, and begin to live our lives in the light of the Great Story. And that is the greatest adventure that can ever befall a human being, because it is what we were made for.

Amherst College MA

April 2007