One of my favorite songs of recent memory is Tom Waits’ Chocolate Jesus because it so well captures and subverts our Western culture’s obsession with do-it-yourself “spirituality” (a nefarious term which, by the way, now only functions as a short form for “anything goes”). With his distinctive voice, once described as sounding “like it was soaked in a vat of bourbon left hanging in the smokehouse for a few months, and then taken outside and run over with a car”, Waits sings:

Well it’s got to be a chocolate Jesus

Make me feel good inside

Got to be a chocolate Jesus

Keep me satisfied…

When the weather gets rough

Its best to wrap your saviour

Up in cellophane

A sweet, user-friendly, emotionally sensitive Jesus, that’s what we want! I had this song in mind as I watched the recent film, Henry Poole is Here.

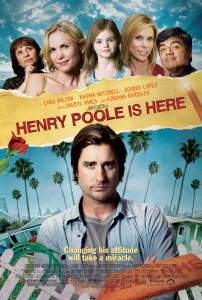

It stars Luke Wilson as Henry Poole and a hodge-podge cast including George Lopez as Father Salazar, a Roman Catholic priest and Adrianna Barraza (of Babel fame where she played Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett’s Mexican nanny) as Esperanza, Mr. Poole’s nosy but well intentioned neighbour.

We meet Henry Poole as a miserable and disillusioned man who goes into hiding in the docile middleclass suburbs where he grew up, seeking anonymity and the bottom of many bottles. He reluctantly buys a blue stucco house across the street from the home in which he was raised (reluctantly because as much as he wants to buy his old home, the family that now lives there won’t sell it to him). And so, he’s consigned himself to a life of seclusion, resentment, and hostility in a house that he is entirely disconnected from.

His isolation is interrupted by Esperanza, his pious Roman Catholic neighbour, who drops by to find out just who it is who moved into the house next door. During her initial visit, Esperanza discovers a water stain on Henry’s outside stucco wall in the likeness of the face of Christ. This discovery quickly, and in some of the most moving scenes of the picture, beautifully and sublimely becomes saturated with claims of miraculous power. This ironically leads to Henry’s eleventh-hour hideout turning into a community shrine.

Henry’s deep cynicism plays out in a series of efforts to rid the wall of the stain and to rid himself of his new ‘friends’ and their faith in this miracle. In fact, for most of the film, Henry is at pains to rid himself of this stucco Jesus as this is a Jesus that Henry definitely doesn’t want. This is not a do-it-yourself Jesus, or a sweet, sensitive, emotionally nurturing Chocolate Jesus but a persistent, relentless, and unyielding Stucco Jesus who completely maddens Henry with his presence.

I won’t give away anymore of the film, but I do want to underscore what this film gets. It gets that God’s grace is often a messy and unexpected thing that interrupts our plans and transforms us in spite of ourselves, especially in spite of our cynicism. The whole gospel message of death and resurrection, of repentance and forgiveness, and of transformation and reconciliation is all played out in this film in and through the face of Christ—which is a rarity indeed.

What else to look for: a stunning performance by one of the supporting cast, Rachel Seiferth as the dorky and inquisitive grocery clerk aptly named Patience.