An evangelism professor looks at the historical evidence, and challenges the popular view that St Francis of Assisi had a low opinion of “using words” in evangelism.

St Francis is supposed to have said, “Preach the Gospel by all means. If necessary, use words.” It has become a rallying cry for those want to downplay the verbal aspect of evangelism, and to increase the importance of social ministries. But the issue is not that clear, and it is questionable whether Francis ever said such a thing.

There has been tension concerning the relationship of words and deeds in Christian witness for two hundred years. There is (quite rightly) a fear that our lives do not live up to the things we say, and a deduction (quite wrongly) that Christians should stick to nonverbal witness. Once our lives are reasonable reflections of the Gospel (whenever that may be) we will dare to speak.

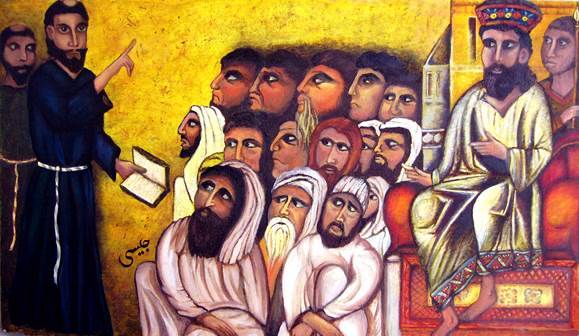

The Francis of history, however, cannot really be used in support of this view. Preaching was central to

Francis’ ministry. One author writes that Francis “went from village to village announcing the kingdom of God, preaching peace, teaching salvation and penance and the remission of sins.”[1] And despite the popular image of Francis as an inoffensive man, his preaching was not marked by gentleness or avoidance of difficult issues. Instead, his critics complained that his preaching was too much of a harangue: no genial, comforting message there.[2]

Having said that, Francis was equally passionate about a lived discipleship that included working towards peace and servanthood. But for him this went hand-in-hand with a verbal proclamation of the gospel. For Francis, the task of Christian ministry was always to represent Christ in word and in deed, and not one without the other.

So where does the famous quotation come from? The first recorded instance comes from around two hundred years after his death—and even there it is an uncited quotation. Today, there is not a single Franciscan scholar who believes this quotation to be authentic to Francis.[3] Instead, the phrase is simply part of the folklore that surrounds Francis. We may like to believe that he said it, but there is no historical evidence.

Four Stories

There are four stories from Francis’ life[4] where he stressed the witness of one’s life over verbal communication, and these may suggest how the saying originated. But in each case, the emphasis was because of specific circumstances—not the statement of a fixed policy.

In the first story, Francis talks with his brothers about the struggle of trying to preach in communities where the local priest forbids them from preaching. The brothers know that they are called to preach the gospel, so are looking for Francis’ permission to defy priests who hinder them.

Francis, who believed in pastoral authority, tells the brothers that when they are prevented from verbal preaching, they are to “preach by their social ministry.” The reason is pragmatic: to keep their ministry under the authority of the local priest. But what is interesting in the story is the brothers’ desire to preach and assumption that this is what they would normally do. Only when this becomes impossible is it acceptable to “preach with one’s life.” They took it for granted that preaching by one’s words and preaching by one’s life are not the same thing.

In a second story, Francis took some of his brothers to a village where they had ministered previously. Before setting out, he told the brothers that the purpose of the visit was to preach. But on this occasion, Francis and the brothers simply walked through the village and out the other side without saying a word. When the brothers inquired why they did not preach in the village, St. Francis told them, “We did preach.”

But the context makes it clear that this is not to show that life-preaching is superior to word-preaching. The witness of their mere presence on this occasion would have reminded those who saw them of other times when they had preached verbally. There was no question in the minds of those who saw the brothers of either their purpose or the Christ whom they represented. Their “evangelism of presence” on this occasion was effective only because of their evangelistic preaching on previous visits.

A third story has to do with Francis’ comments on the haughtiness of a certain academic. This academic apparently knew something of the gospel and was known as an eloquent preacher. Unfortunately, it was known that he failed to live out the faith he proclaimed. So Francis warned his brothers of the dangers of knowing the faith but not living it: “If he is a scholar himself, far from priding himself on his learning, let him be diligent above all to be humble and simple, endeavoring to preach by example rather than by word.”

In this case also, Francis is not commending preaching by one’s life as a substitute for verbal proclamation. Rather, the testimony of a Christian’s life is a sign that one really believes the gospel. This story simply shows that both living and speaking the gospel are critical to Christian discipleship. One cannot be substituted for the other.

The fourth and perhaps most dramatic story took place in 1219 during the crusades, when he traveled to the Holy Land to preach the gospel to the Muslims, seeking peace and conversion.

At one point he was given a pass through the enemy lines, whereupon he went to the Sultan, Melek-al-Kamil. Francis preached to the Sultan and told him the story of Jesus Christ. The Sultan replied that he had his own beliefs, and that Moslems were as firmly convinced of the truth of Islam as Francis was of the truth of Christianity.

In response, Francis proposed that a fire be built, and that he and a Moslem volunteer walk side-by-side into the fire to show whose faith was stronger. When the Sultan said he was not sure a volunteer could be found, Francis offered to walk into the fire alone. The Sultan was deeply impressed but remained unconverted.

Before Francis left, he proposed to the Sultan an armistice between the two warring sides. He drew up terms for peace to which the Sultan agreed, but unfortunately the Christians did not.

These stories may be the basis for the phrase so often attributed to St. Francis regarding preaching with one’s life. Virtually every other example from Francis’ life and ministry, however, including stories of his preaching to the animals in the forest, demonstrate how important he believed verbal proclamation of the gospel to be. These four stories actually solidify the idea that verbal proclamation is the critical act of evangelistic ministry.

Conclusion

St. Francis thus gets it right—but the phrase we associate with him fails to express the fullness of his ministry. Both verbal proclamation and social ministry are critical to the church’s mission and to an individual Christian’s discipleship. The gospel must be announced both to those who have heard it and those who have not. In turn, this announcement leads to a profound love of God and humanity that results in radical service to humanity. This service is valid in and of itself, but it also serves to confirm the authenticity of a believer’s faith.

The evangelistic task itself, as modeled by St. Francis, is an essentially verbal task that is critical to the church’s overall ministry. The relationship between social ministry and evangelism is not that social ministry is a form of evangelism, but that both are critical aspects of ministry. Mission and discipleship take place in word plus social ministry, not word or social ministry.

Jack Jackson is E. Stanley Jones Associate Professor of Evangelism, Mission, and Global Methodism at the Claremont School of Theology in California.

[1] R.G. Musto, Catholic Peacemakers: A Documentary History (New York: Garland Publications, 1993), 490.

[2] Ibid, 519.

[3] Pat McCloskey, “Where Did St. Francis Say That?” St. Anthony Messenger: Ask a Franciscan, September 18, 2008. http://www.americancatholic.org/messenger/Oct2001/Wiseman.asp.

[4] The stories that follow are to be found in M.A. Habig, St. Francis of Assisi: Writings and Early Biographies: English Omnibus of the Sources for the Life of St. Francis (Chicago, IL: Franciscan Herald Press, 1983).