In this second of a two-part series, I continue to explore how viewing conversion as the formation of a relationship with God helps us reframe our efforts to share the gospel as churches and individuals. [Click here] to read the first article.

Does becoming a Christian mean accepting a set of beliefs or doctrines? Is it an emotional or spiritual experience that happens to a person? Or is it a choice they make? Or does it have more to do with being baptized and joining the church? How we answer these questions has a profound effect on the way we share the gospel, as churches and individuals.

Last month we began to explore the idea of conversion as reconciliation. Paul explains that “while we were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to him through the death of his Son” (Romans 5:10). In other words, the distance from God we once experienced is being replaced by closeness and friendship. As we explored last month, this is not a one-time event but a process that unfolds step by step over time—just as in human relationships.

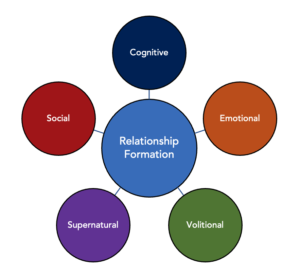

However, not only is relationship formation progressive, it is also multifaceted. It affects many aspects of life, including: cognitive, as knowledge is gained of the other person; emotional, as affection and fondness take root; volitional, as decisions are made to invest in the relationship and change in response to it; and social, as each person gets to know the friends and family of the other.

Each of these elements plays an essential role in the formation of a relationship. If two people in a romantic relationship do not know each other, no matter how strong the feelings of attraction are, their relationship is not healthy. On the other hand, if they know everything about each other, but do not like each other, or refuse to compromise, or never join each other’s social circles, their relationship is on shaky ground.

Human relationships are wholistic, integrating many aspects of life. The same is true of a relationship with God. However, when we think about conversion (and evangelism), we tend to emphasize just one area of transformation. In fact, most of our ways of framing what it means to become Christian fall into one of five models of conversion:[1]

However, when we think about conversion (and evangelism), we tend to emphasize just one area of transformation. In fact, most of our ways of framing what it means to become Christian fall into one of five models of conversion:[1]

- The cognitive model views conversion as coming to believe a certain set of beliefs or doctrines. Education and argumentation are therefore essential tasks for the evangelist. Introductory classes and apologetics are especially important tools within this model.

- The emotional model looks for an affective experience—a Damascus Road vision (like Paul) or a “heart strangely warmed” (like John Wesley). Evangelism, then, focuses on stirring up emotions that will lead the person toward Christ. Both modern experiential worship and traditional revival services focus on this aspect.

- The volitional model primarily sees becoming a Christian as a decision to be made. Evangelism, therefore, targets the human will through persuasion. Billy Graham called for people to make a “decision” for Christ, and many evangelistic approaches of the last fifty years have likewise emphasized this aspect.

- While the previous model focuses on the human side of the relationship, the supernatural model accentuates the divine. God does the quickening and regenerating by his own initiative, and this is what matters most. In this model, human evangelists are responsible for proclaiming the gospel, but the results are entirely in God’s hands.

- The social model closely associates becoming a Christian with joining the church, so efforts centre around the convert’s incorporation into the community through social connection and entrance rites, especially baptism. The outreach efforts of many mainline churches are built around this communal component.

Each of these models captures one piece of what it means to become a Christian. However, we intuitively know that there is more to conversion than simply assenting to Christian beliefs, having an emotional experience, or encountering any one of the other aspects on its own.

Looking at conversion as reconciliation can give us a more complete vision for what it means to become a Christian. This “relational model” incorporates all five elements of conversion—cognitive, emotional, volitional, supernatural, and social—into the wholistic process of forming a relationship with God. It also allows room for each of the above approaches to evangelism, giving them all a role to play in the larger objective.

This framework can help individuals become more aware of the needs of those they are sharing their faith with. Evangelists can consider which aspects of a relationship with God are already developing in the other person, and which are missing. They can also identify the aspects of evangelism they gravitate toward—and ask for help in areas of weakness. For example, if someone has a strong emotional connection with God, they will likely emphasize this in their evangelistic efforts. However, if the person with whom they are sharing has intellectual questions, they can enlist the help of a friend who is interested in apologetics and the more cerebral side of Christianity.

This way of looking at conversion can also help churches analyze their congregation’s overall strategy. Stronger and weaker areas can be identified, and efforts made to fill in missing gaps. For example, a church may welcome spiritual seekers effectively (social), offer a well-attended introduction to Christianity class (cognitive) and foster an environment for passionate worship (emotional). However, if they do not regularly call people to “repent and be baptized” or give opportunities to make a commitment to Christ, they will miss the important volitional aspect of the conversion process. Incidentally, this framework also helps to explain the effectiveness of the Alpha course, which gives attention to all five aspects.

Just like a healthy marriage, a relationship with God is complex, multifaceted, and constantly growing. This is just as true at the beginning as it is at the twenty-fifth or fiftieth anniversary. Which aspects of your own relationship with God are strongest and weakest right now? How might God use your own growth and development in those areas (or others) to help those who are just getting started? How can you partner with those who are strong in different areas to create a more wholistic approach to helping people become Christians?

[1] These five models are not necessarily exhaustive. They emerged as a way to organize the various perspectives I encountered while researching conversion for my MA thesis. While we are focusing here on Christian perspectives, they can also be helpful for categorizing secular scholarship on conversion. E.g., anthropologists focusing on changes in worldview are highlighting the cognitive element of conversion, whereas Freudian psychoanalysts view it as an emotional event.