Closer Than You Know – The movie Never Let Me Go holds a searing lesson in bioethics we must heed today.

Imagine yourself a cloned child created from the DNA of a wealthy person who wants to have your organs available for transplant, when he later needs them. The only life you know as a child is as one of a large number of other clones who are kept in the setting of an isolated English boarding school, Hailsham, where none of you has any contact with the outside world. Initially, you have no idea of your intended destiny, as an organ donor.

Imagine yourself a cloned child created from the DNA of a wealthy person who wants to have your organs available for transplant, when he later needs them. The only life you know as a child is as one of a large number of other clones who are kept in the setting of an isolated English boarding school, Hailsham, where none of you has any contact with the outside world. Initially, you have no idea of your intended destiny, as an organ donor.

At age 18, you leave Hailsham for other supervised accommodation, where you will live until you become an organ “donor,” usually in a sequence of “retrieval operations,” finally being killed when an unpaired vital organ is taken.

In the film of Kazuo Ishiguro’s book, Never Let Me Go, which is playing in Canada, we watch this dystopic and unethical example of a rapidly developing field called “regenerative medicine” (which, used ethically, offers great hope), being played out against a tragic love story that involves three of these young people. Through this love story, we understand how fully human they are, in contrast to the immense dehumanization to which they are subjected.

Reviewers have commented that the film is unusual in being a science-fiction story set in the past, the 1950s and ’60s. But what makes it so spine-chilling is that we come to realize that our present world is the future Ishiguro describes. Many scenarios it portrays, such as organ transplantation, and genetic and reproductive technologies, which were unknown in the ’50s and ’60s, are now science-fact. The film delivers a powerful message that we need to become much more sensitive than we currently are to the ethics issues 21st-century technoscience raises.

Here are some of the lessons we can take from it.

The cloned children are regarded by the people who run their school as repositories of organs rather than as individual persons, as objects, not human subjects. This dehumanization is inflicted both through the way in which the children are treated and language.

They are constantly monitored with electronic bracelets, like animals are with computer chips. One supervisor, obviously meaning to be empathetic, remarks, “you poor creatures.” Creatures is a word we use to refer to animals, usually when we are differentiating them from humans. And someone queries whether they have a soul. What is clear is that in dehumanizing the children, these people dehumanize themselves more.

A major current example of dehumanization through language involves human embryos and fetuses. Human embryo research is justified by describing the embryos as “just a bunch of cells” and, in abortion, fetuses are characterized as “just unwanted tissue, part of the woman’s body, not a child.”

The physicians and nurses responsible for keeping the children healthy, so later their organs can be used, also dehumanize them. In medically examining them, they act as though they are mechanics making sure a car is in good running order, not health-care professionals caring for patients. Most horrific in this regard, is the scene showing surgeons undertaking a vital-organ-retrieval-operation that kills the “donor.” They carefully take the organ, then instantly “pull the plug” on both the life support technology and any engagement with the “patient,” simply walking out leaving the dead body on the operating table, bleeding, not even bothering to suture the wound. Even in death the person is not respected as human.

Who were these physicians and nurses? How could they be in involved in such evil, such appalling violation of medical ethics? That same question has often been asked by scholars in relation to the Nazi doctors in the death camps. Are comparable unethical operations taking place in some countries today, for instance, using prisoners as “donors”? Might some Canadians be recipients of these organs?

How could society allow this to happen? Why wasn’t it prohibited and severely punished? Or was society complicit in the evil by funding the technoscience that made it possible, without ensuring that technoscience was used only ethically?

Who were the scientists who made the clones and what ethical requirements should have governed them?

And where were society’s watchdogs, the medical and scientific bodies responsible for ensuring ethics in the professions? Or was it a situation where the legislated safeguards were inoperative.

It’s clear in the book that “farming” these children is a lucrative commercial industry. This brings to mind the “fertility industry” that markets assisted reproductive technologies, bringing in $3.3 billion annually, in the United States alone. It’s an area that needs very close ethical supervision, yet it’s common to hear it referred to as the “Wild West of human reproduction.” Note also the unethical international organ transplant industry that the recent Declaration of Istanbul seeks to eliminate.

Another warning comes from the intentional use of euphemistic or obfuscating language by those involved in the “cloning-transplant project.” Euphemisms can skew our perceptions about ethics, probably by suppressing moral intuitions that clear language would elicit and which would function as ethical red alerts.

The person cloned, is referred to simply as the clone’s “original.” The clones go looking for their “originals.” They describe sighting a person, who might be such, as seeing a “possible.” Especially in the book, Ishiguro captures, exactly as I’ve personally heard donor-conceived people express it, their anguish at not knowing, but longing to know, their biological antecedents.

The word “kill” is never used and even the word “death” is avoided, as is often true of pro-euthanasia advocates. Rather, the final fatal surgery is referred to as a “completion.” A nurse remarks that “some donors look forward to completion,” which is not surprising seeing the immensely debilitated state of the young people, who have already made multiple donations. Towards the end of the film, the former headmistress of Hailsham, now retired and in a wheelchair, remarks, philosophically, “that we all have to complete sometime.” That’s true, but how we “complete” is the critical ethical issue, as we can see in the present euthanasia debate.

That brings us to convergence, which refers to interventions that become possible only through the combination of separate technologies. Never Let Me Go is a story of the convergence of genetic and reproductive technologies — cloning, in vitro fertilization and surrogate motherhood — and organ transplant technologies.

Each technology, taken alone, raises serious ethical issues, but combined they raise ethical issues of a different order, as we see in Never Let Me Go. And such issues might be closer to us, than most of us realize.

Is it ethical for people who are euthanized, in countries where this is legal, to become organ donors? There have been recent reports of this at transplantation conferences and in the medical literature.

And here’s another presently possible scenario of convergence, the only element of which is illegal in Canada would be cloning the embryo, which advocates of human embryo research have argued should be allowed for “therapeutic purposes”: Create an in vitro embryo and take one cell, when all cells are still totipotential (can form another embryo) to make a second embryo. Transfer the first embryo to a woman’s uterus and freeze the second embryo. When, as a born child or adult, the first embryo needs an organ transplant, transfer the second embryo to a surrogate mother, abort the fetus at a late stage and use its organs.

Finally, a statement from the wheel-chair-bound ex-head mistress of Hailsham merits noting with respect to the philosophy and values on which we should base our ethics. It shows her exclusively rational approach to the horror of what she helped to inflict on the children in her charge.

Two of them, who are now adults and in love, come to her seeking a deferral of the “completion” organ retrieval surgery on the young man, so they can have some time together before he is killed. She tells them that is not possible and enquires, rhetorically, “Would you ask people to return to lung cancer, heart failure and other terrible diseases?”

Never Let Me Go is a searing lesson about the “ethics outcomes” that can result from pure utilitarianism and moral relativism, when they are used to govern the new technoscience by people without a moral conscience or moral intuition.

Margaret Somerville DCL, LL.D, is the founding director of the Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law at McGill University.

Printed with permission of the author.

This article was first published in the Ottawa Citizen

C.S.Lewis’ The Voyage of the Dawn Treader – Coming to a Cinema near You on December 10

I have an actor friend, Joe Abbey-Colborne, who worked with me in campus evangelism nearly twenty years ago. When I first suggested a collaboration to him, he was nervous. He had had too many experiences of doing dramatic sketches, then having a preacher stand up and say, “Now, I hope you understand that this character represents Jesus, and that the lesson the sketch holds for us is the following.” I promised I would never do anything of the sort.

I have an actor friend, Joe Abbey-Colborne, who worked with me in campus evangelism nearly twenty years ago. When I first suggested a collaboration to him, he was nervous. He had had too many experiences of doing dramatic sketches, then having a preacher stand up and say, “Now, I hope you understand that this character represents Jesus, and that the lesson the sketch holds for us is the following.” I promised I would never do anything of the sort.

C.S.Lewis had similar worries about The Chronicles of Narnia. He was emphatic that the Narnia stories are not an allegory, like Pilgrim’s Progress, or even his own Pilgrim’s Regress, where a is meant to represent b, and c to represent d. They are rather, he suggested, a “supposal.” Suppose that the God who created our world created life on other planets, and suppose that this God chose to communicate with them, what that communication look like? Naturally, there would be similarities to our experience of God in our world—we might recognise something of the same flavour—the same style if you will—of God as we know God in Jesus Christ. And yet it would be distinctive.

As a result, with the exception of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the first (and, I would argue, the weakest—he got better as he went along) of the books, while we may recognise Christian themes in Aslan’s dealings with the Narnian world (his loving strength, his demand for trust, his willingness to be intimate with his creatures), there are few one-to-one correspondences with the story of God as we know it.

His goal, he told his friend George Sayer, was “a sort of pre-baptism of the child’s imagination.” Sayer comments, “His hope was that when, at an older age, the child came into contact with the real truths of Christianity, he or she would find these truths easier to accept because of reading with pleasure and accepting stories with similar themes years before.” [1]

In a sense, Lewis is giving his readers the opportunity to follow the course of his own spiritual journey: raised in the Anglican church, but finding it lifeless, and turning instead to atheism; having experiences of “joy” through reading pagan mythology; and finally returning to Christian faith (and Anglicanism) by realising (with the help of his friend Tolkien) that the mythology he had loved was really pointing him beyond itself to a depth in Christianity—the true joy—that he had never known as a child. The Chronicles seek to circumvent the “watchful dragons”[2] too often associated with “religion.”

Naturally, there are few hints in the Chronicles themselves that this is Lewis’ goal. That would be to subvert his intention—not to say ruin a perfectly good story. But in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, he gives two very strong hints of what he is about.

One takes place when Lucy is in the magician’s house on the Island of the Voices, reading through the book of spells. She comes across a story “for the refreshment of the spirit,” which takes up three pages and tells “about a cup and a sword and a tree and a green hill.” She says, “That is the loveliest story I’ve read or ever shall read in my whole life.” Yet as soon as the story is done, she cannot recall it, nor can she turn the pages back. She asks Aslan, “Will you tell it to me, Aslan?” And he says, “Indeed, yes. I will tell it to you for years and years.”[3] For the thoughtful reader, it raises the question of where Lucy might find such a story in our world. Christian readers already know.

The other place is right at the end of the book, when the children are about to return to their own world, and Lucy weeps because (she thinks) they will never see Aslan again. Aslan says, “But you shall meet me, dear one.” Edmund doesn’t understand: “Are—are you there too, sir?” To which Aslan replies:

“I am . . . But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. That was the very reason you were brought into Narnia, that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.”[4]

Again, Lewis is putting a grain of sand into the oyster of the reader’s mind: what on earth is Aslan’s “other name” in our world? How can we possibly know the fictional Aslan in our own world? How can there have been a this-worldly “purpose” to our reading about Narnia? Lewis is not going to tell us: but he wants us to think about it, and (with the help of the Spirit) to discover the answer.

Lewis is a good evangelist—clear about The Story but respectful, winsome and imaginative in how he presents it, seeking a response and yet encouraging us to figure it out for ourselves. We could do worse than to follow his example. And maybe the movie—if it as faithful to the book as it is supposed to be—will be helpful to us in our own evangelism.

[1] Sayer, George, Jack: A Life of C.S.Lewis (Wheaton IL: Crossway Books, 1994), 318, 419-420.

[2] Lewis, C.S. “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said”, in Of This and Other Worlds (London: Collins Fount Paperbacks, 1984), 72.

[3] Lewis, C.S. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (Harmondsworth: Puffin Books, 1965), 134, 137.

[4] Ibid., 209.

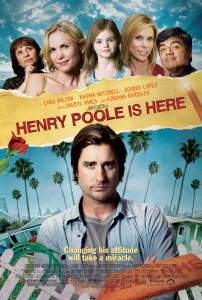

Stucco Jesus: a Review of Henry Poole is Here

One of my favorite songs of recent memory is Tom Waits’ Chocolate Jesus because it so well captures and subverts our Western culture’s obsession with do-it-yourself “spirituality” (a nefarious term which, by the way, now only functions as a short form for “anything goes”). With his distinctive voice, once described as sounding “like it was soaked in a vat of bourbon left hanging in the smokehouse for a few months, and then taken outside and run over with a car”, Waits sings:

Well it’s got to be a chocolate Jesus

Make me feel good inside

Got to be a chocolate Jesus

Keep me satisfied…

When the weather gets rough

Its best to wrap your saviour

Up in cellophane

A sweet, user-friendly, emotionally sensitive Jesus, that’s what we want! I had this song in mind as I watched the recent film, Henry Poole is Here.

It stars Luke Wilson as Henry Poole and a hodge-podge cast including George Lopez as Father Salazar, a Roman Catholic priest and Adrianna Barraza (of Babel fame where she played Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett’s Mexican nanny) as Esperanza, Mr. Poole’s nosy but well intentioned neighbour.

We meet Henry Poole as a miserable and disillusioned man who goes into hiding in the docile middleclass suburbs where he grew up, seeking anonymity and the bottom of many bottles. He reluctantly buys a blue stucco house across the street from the home in which he was raised (reluctantly because as much as he wants to buy his old home, the family that now lives there won’t sell it to him). And so, he’s consigned himself to a life of seclusion, resentment, and hostility in a house that he is entirely disconnected from.

His isolation is interrupted by Esperanza, his pious Roman Catholic neighbour, who drops by to find out just who it is who moved into the house next door. During her initial visit, Esperanza discovers a water stain on Henry’s outside stucco wall in the likeness of the face of Christ. This discovery quickly, and in some of the most moving scenes of the picture, beautifully and sublimely becomes saturated with claims of miraculous power. This ironically leads to Henry’s eleventh-hour hideout turning into a community shrine.

Henry’s deep cynicism plays out in a series of efforts to rid the wall of the stain and to rid himself of his new ‘friends’ and their faith in this miracle. In fact, for most of the film, Henry is at pains to rid himself of this stucco Jesus as this is a Jesus that Henry definitely doesn’t want. This is not a do-it-yourself Jesus, or a sweet, sensitive, emotionally nurturing Chocolate Jesus but a persistent, relentless, and unyielding Stucco Jesus who completely maddens Henry with his presence.

I won’t give away anymore of the film, but I do want to underscore what this film gets. It gets that God’s grace is often a messy and unexpected thing that interrupts our plans and transforms us in spite of ourselves, especially in spite of our cynicism. The whole gospel message of death and resurrection, of repentance and forgiveness, and of transformation and reconciliation is all played out in this film in and through the face of Christ—which is a rarity indeed.

What else to look for: a stunning performance by one of the supporting cast, Rachel Seiferth as the dorky and inquisitive grocery clerk aptly named Patience.

Gospel Themes in Slumdog Millionaire

Slumdog Millionaire is a 2008 British film directed by Danny Boyle, written by Simon Beaufoy, and co-directed in India by Loveleen Tandan. It is an adaptation of the Boeke Prize-winning and Commonwealth Writers’ Prize-nominated novel Q & A (2005) by Indian author and diplomat Vikas Swarup.

Slumdog Millionaire is a 2008 British film directed by Danny Boyle, written by Simon Beaufoy, and co-directed in India by Loveleen Tandan. It is an adaptation of the Boeke Prize-winning and Commonwealth Writers’ Prize-nominated novel Q & A (2005) by Indian author and diplomat Vikas Swarup.

If you are not familiar with the film the synopsis can be found on Wikipedia. I want to restrict my review to the film as a context for raising Gospel issues with friends.

Firstly, the film presents us with opportunities to talk about child exploitation, not only in India but globally. Deliberately acquiring orphans to maim them for begging or to groom them for sexual abuse is a subject we might find abhorrent but nothing is beyond the degradation of sinful humanity. In a post-modern society we need to engage with a public who are still interested in the concept of “evil”.

Secondly, the film deals with a “worldview” that embraces destiny (kismet) that engenders fatalism. As all the central characters in the film (apparently not in the book) are Muslim; Jamal, Salim, and Latika, this destiny is within the context of Islam. The very end screen has the words, D: It is written (translated from the Arabic “maktuub”). The meaning of life is not a very popular subject in the West but as cultures collide in our multi-cultural pluralistic societies we need to address the subject, if not for our own reflection certainly for our dialogue with others.

Thirdly, the two characters of Jamal and Salim seem to represent good and evil. Following the failure of torture to find out how Jamal is cheating (the opening film’s sequence), his “innocence” is unpacked during his subsequent interrogation by the police inspector. During the cross-examination the naive ability of Jamal to answer the quiz questions is revealed as his “destiny”. Several of his life experiences provide the exact answers. When there has been no such experience Jamal trustingly chooses the correct answers. Thieving is either sanitized as justifiable for the two boys’ survival, e.g., duping wealthy tourists at the Taj Mahal, or Jamal is the blameless bystander of violence, e.g., the shooting of Maman by Salim. His gentle compassion towards Latika from the beginning speaks of “purity” and “protection”. Even his adult job as a “chai-wallah” (tea boy) in a telephone call centre (very contemporary) enhances his “virtuousness”.

On the other hand his older brother, Salim, could be interpreted to represent evil. He is the one who shoots Maman, who joins a protection racket run by Javed and eventually gets killed. The final scene in Javed’s safe house is of Salim lying in a bath that is filled with paper money. One cannot help thinking that here is a symbolic representation of the words, “The wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23). In spite of Salim’s propensity for violence, brotherly love prevails at the most critical moments. And others may propose that Salim, in liberating Latika and dying in the process, has a redemptive role.

Fourthly, the film is a good Bollywood sampler for the Western viewer. Simply the Eastern exposure that it provides the Westerner is a good reason for seeing the film. It is a love story. Across the some 20 years that the flashbacks cover the pursuit of Latika is the thread. The climax of the film is not so much the winning of the 20 million rupees but their uniting. Reunited at Mumbai’s main train station the film credits begin to roll as they dance together in truly Bollywood style with a choreographed troop of dancers.

In the Indian context of relative poverty, exploitation and degradation, it is also a victory of the underdog (the slumdog) to overcome every attempt by the social context to subjugate and destroy the human spirit. This is depicted in the film through the rising public interest of the masses in the TV programme. It is the Bollywood happy ending of love conquering all.

Like all award-winning films there are many other themes and sub-texts running through the story that can be discerned but concentrating on these four will give the Christian opportunities to talk of the eternal truths of the Gospel; sin, the purpose of life, the God of creation, redemption, love, hope, and justice.

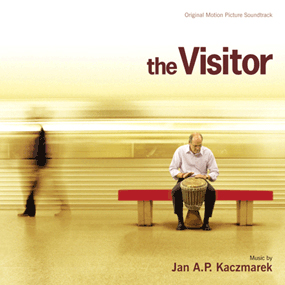

Revisiting Hospitality: A Review of “The Visitor”

Last year’s Oscars were all about the dark and the tragic with No Country for Old Men and There Will be Blood going home with some of the top nods (two of my favorite movies last year, by the way). This year’s Oscars were more light-hearted—there wasn’t much of the tragic with Brad Pitt as Benjamin Button or with the runaway indie hit, and Oscar’s little darling Slumdog Millionaire. There was, however, one nomination this year for best actor that, if you weren’t paying attention, was easy to overlook.

Richard Jenkins, who played the dead father in HBO’s Six Feet Under, stars in one of last year’s best films, The Visitor. This is Jenkins’ first major lead as he’s been playing supporting or character TV roles for the last thirty or so years (most recently as the gym manager in Burn After Reading). Jenkins plays Professor Walter Vale, a quiet, self-loathing, and eminently bored economics professor who’s entirely dissatisfied with his life. Widowed, Vale spends his down time trying to learn the piano in an effort to emulate his late wife, a classical concert pianist. He’s been giving the same lectures for years on end, just changing the date on them so that nobody catches on.

By a turn of events, his department head forces him to go to an academic conference to read a paper he nominally co-authored (which he hadn’t even read!) when the primary author backs out. When Walter arrives at the apartment he maintains in Manhattan, he’s startled to discover a young couple living there. The young man Tarek, a Syrian djembe drum player and his girlfriend Zainab, a Senegalese jewelry maker were conned into subletting his apartment and were equally surprised by this intrusion! In an act that shocks Walter as much as it does Tarek and Zainab, he asks them to stay while they figure things out.

A friendship ensues between Walter and Tarek over the next few days. Tarek teaches Walter to play the djembe drum and, in one of the most poignant scenes of the film, they both join a drum circle in Central Park. On one occasion as the pair travel the subway with their drums in hand, Tarek is mistakenly charged (profiled?) with turnstile jumping (not paying for the subway) and is arrested. The thing is, Tarek along with Zainab (and as we learn later, Tarek’s mother, Mouna) is an illegal immigrant. He is held in a detention center downtown and Walter finds a new energy in his life as he advocates for Tarek, hires an immigration lawyer and befriends Tarek’s mother. Walter and Mouna being to develop a deep friendship as together they await Tarek’s fate.

While this movie deals with the larger realities of immigration, identity, and cross-cultural communication, it is, at bottom, a movie about radical hospitality. Walter learns the truth of his life when he steps into somebody else’s, or rather, when they step into his. As the church, in our geo-political, post-9/11 reality, we hear much about the immigration “problem”. Tersely, these so-called problems—an increase in crime, an increase in job losses, an increase in language barriers (to name a few)—are said to accompany the rise in immigration. Tom McCarthy, the writer and director of the film, doesn’t tip-toe around this, but rather puts the issue right into the space that Walter rightfully ought to occupy—his own apartment!—and so throws the issue of the ‘other’ into sharp relief, bringing it right to our doorstep.

Walter has two options available to him: security or the vulnerability of hospitality. He can call the police; he can secure his home against the otherness and all the difference that accompanies the intrusion. Or he can embrace the difference; he can accept the otherness of the intrusion and so witness the transformation of the other into a neighbour, into a friend. Indeed this is what happens and Walter learns that this transformation is not only objective—that these people have turned into his neighbours—but entirely subjective as well, as he realizes that he has become a neighbour; he himself transforms into a friend to these strangers. That’s what the practice of hospitality does.

Christ’s call to neighbour-love is a call to radical hospitality in all its messiness; it’s a call to welcome the stranger to our table, to Christ’s table, no matter what the barrier might be. Now this might sound cliché and somewhat overstated, but when we have an analogy of the church in the figure of Walter Vale played out for us on the screen, this cliché gets some traction.

The church, in its everyday existence—the church of parking lots and potluck suppers (to borrow a phrase from Stanley Hauerwas)—continually wavers between extending hospitality and an illegitimate concern over its own security. The church, with its narcissistic tendencies, tries again and again to protect itself against the intrusion of the stranger, against the presence of the different. We tend to circle the wagons, as it were, around our little corner of the truth. When we do this we obscure our witness; when we sit in self-concern, we block out the presence of the crucified Christ—we simply deny that the Kingdom of God is come. Yet, when the church opens itself to the messiness of hospitality, the Kingdom is played out in the middle of our messes. This movie embodies that openness and so is a wonderful analogy of God’s reign among us.

Documentary Now Available: “One Size Fits All?” – Exploring New and Evolving Forms of Church in Canada

Church Planter and Filmmaker Joe Manafo’s 43-minute documentary on new and evolving forms of church in Canada, One Size Fits All? has just been released on DVD and is available for sale at http://www.onesizefitsall.ca/. Manafo visits fresh expressions of church across Canada, including Emerge and St. Benedict’s Table, Anglican fresh expressions of church in Montreal and Winnipeg. There will be a screening of One Size Fits All at the Vital Church Planting Conference February 17-19, 2009.

Church Planter and Filmmaker Joe Manafo’s 43-minute documentary on new and evolving forms of church in Canada, One Size Fits All? has just been released on DVD and is available for sale at http://www.onesizefitsall.ca/. Manafo visits fresh expressions of church across Canada, including Emerge and St. Benedict’s Table, Anglican fresh expressions of church in Montreal and Winnipeg. There will be a screening of One Size Fits All at the Vital Church Planting Conference February 17-19, 2009.

From http://www.onesizefitsall.ca/ –

What is God doing on the fringes of Canadian culture? Flying under the radar of pop-Christianity, experimental churches are quietly establishing genuine Kingdom outposts in settings both feared and forgotten. ‘One Size Fits All?’ uncovers the obscure story of these Canadian missional communities and its leaders.

Watch the video below for a short preview:

Taking Offence, or why Paul would have been a Monty Python fan

I came across an article in TimesOnline about a month ago now. It was a top twenty list of the most religiously offensive cultural moments of the last thirty or so years. The article, “The Blasphemy Collection” listed one of my personal favorites. Monty Python’s Life of Brian was there with its infamous protagonist, Brian Cohen, who, being born in the stable next to Jesus’, spends the rest of his life mistaken for the Messiah. Especially offensive in this one is the final crucifixion scene where those being executed burst into song, “Always look on the bright side of life” with Eric Idle playing the lead singer crucifee. What I didn’t realize was that this film wasn’t officially shown in some countries for years after it was made (in Ireland it took 8 years, in Italy 11 years!) because of the offence it caused to some Christian groups.

I came across an article in TimesOnline about a month ago now. It was a top twenty list of the most religiously offensive cultural moments of the last thirty or so years. The article, “The Blasphemy Collection” listed one of my personal favorites. Monty Python’s Life of Brian was there with its infamous protagonist, Brian Cohen, who, being born in the stable next to Jesus’, spends the rest of his life mistaken for the Messiah. Especially offensive in this one is the final crucifixion scene where those being executed burst into song, “Always look on the bright side of life” with Eric Idle playing the lead singer crucifee. What I didn’t realize was that this film wasn’t officially shown in some countries for years after it was made (in Ireland it took 8 years, in Italy 11 years!) because of the offence it caused to some Christian groups.

There were some other more arcane moments in this top twenty, like the artist Cosimo Cavallaro’s My Sweet Lord, a 200lb figure of the crucified Christ carved entirely out of chocolate, which was pulled from a New York art gallery after protest from the Catholic League during Holy Week earlier this year.

Now there were also some whose vulgarity even shocked me (which, I must admit, takes a bit of work), but I’ll save you from those (just follow the link, if you’d like). What I want to get at is that it’s easy to be offended when we feel as if our faith is being ridiculed, or when we feel as if the profane is encroaching too close to the sacred. It’s sort of a natural reaction. St. Paul, though, had a different idea. For St. Paul, the cross is an offence; the sacred is profaned in the reality of the cross of Jesus. Here’s Paul, writing to the congregation at Corinth:

For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God…. we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are…

It’s a bit of a cliché to say that the church has domesticated the message of the cross, but I’ll say it anyways. Imagine for a moment, if you will, that this coming Sunday, instead of a cross sitting atop the steeple of your church as you’re walking in, there was, in its place, an electric chair. Digest that for a minute. Then, when you walk inside, this common symbol of execution is all over the place, even hanging around the necks of some of the people inside. How many of you would voluntarily associate yourselves with such an offensive place and with people like this? Well, given that you’re reading this, you probably do so on a weekly basis. Maybe now you can appreciate a little better this “foolishness” the apostle is talking about.

Perhaps it takes some of our artists, poets, writers, and film makers—the best of religion’s cultured despisers—to remind us, as St. Paul reminded the believers at Corinth, that what we’re all about is, at first, second, and maybe even third glance, foolish. And why foolishness? Why does Paul use this language? Not because, it seems to me, he wanted to delight in the absurd (after all, he was a fairly reasonable person), or even because he wanted to confound conventional wisdom, but because, for Paul the God who is revealed at the cross, the God who is revealed in weakness and death, is, by all appearances, a fool (how’s that for offensive?)!

And we’re called to follow this God, this Jesus in this way, in a way that seems to be a fool’s game, at least according to the rules of this world. This crucified God is an offence. This God offends our sense of what we ought to value, of what’s up and of what’s down. Power, strength, security, and success are the goals of the game according to our pervasive culture of entitlement. But this God has changed the rules, upended our game, and has showed us, from the darkness and offence of the cross, the true bright side of life.